Remembering David Oluwale

By Max Farrar

The David Oluwale Memorial Association banner [design: Sai Murray]

Why does a Nigerian Vagrant who drowned in Leeds, England, in 1969 Matter?

There are lots of reasons why David Oluwale, hounded to his death in Leeds in 1969, matters. All lives matter. Black lives in racist societies matter especially because they are emblems of what is right and what is wrong in those societies. It is upon black bodies that tragedies and (sometimes) triumphs are marked. The David Oluwale Memorial Association (DOMA) is producing a narrative which explains David Oluwale as much more than a victim of terrible abuse. We see him as a Nigerian-British man with agency, defiant of the extraordinary oppression he went through in the 1950s and 60s in the north of England.

David Oluwale arrived on the Motor Vessel Temple Bar on 4th September 1949 at the port of Hull on the north east coast of England. He and two others had stowed away and evaded detection at Apapa Wharf in Lagos, Nigeria, but they were found during the voyage. David was among the 1,600 stowaways estimated to have arrived in Britain between 1945 and 1951, two-thirds of whom came from West Africa and the rest from the West Indies. 83 other stowaways were found between 1948 and 1949 in Hull.[1]

Sentenced to a month in jail for breaching maritime regulations (by not buying a ticket), David was transferred to Armley Jail in Leeds, West Yorkshire. He spent most of his next twenty years in Leeds. He had come to England to escape low-pay or no-pay in Nigeria, with the mother country in mind. His first few years went as well as a black man who left school at 14 could expect in a far from motherly country.

After four years of hard labour, David experienced police brutality, mental ill-health, racism, incarceration, destitution and homelessness. His British citizenship conferred very little; in many ways he was like today’s refugees. But he never gave up. The appalling treatment he received from the police, probation, mental health, welfare and homelessness services requires an intersectional understanding of social issues, and provides a clarion call for inclusive and hospitable responses to those who still endure lives like David’s.

Police brutality

The trial, in November 1971, of two police officers accused of the manslaughter and actual and grievous bodily harm of David Oluwale lasted for two weeks in Leeds Crown Court. In those days the court was part of the city’s magnificent Town Hall. Chief Superintendent Perkins, who led the meticulous investigation into these crimes, wanted the policemen to be charged with murder, but the Crown Prosecution Service would not have it.

Inspector Ellerker and Detective Sergeant Kitching denied all charges. Kitching admitted that he ‘tickled [Oluwale] with my boot’ as he frequently evicted him from the doorways in which he was sleeping in Leeds city centre. But he claimed he ‘never hit him really hard . . . just a good slapping’. Ellerker said he only used reasonable force when David ‘came at me like a hurricane . . . screaming like a lunatic’. Kitching told the court that David was ‘a wild animal, not a human being’.

David Oluwale’s body had been found in the River Aire, a mile or so out of Leeds city centre, on 4th May 1969 by some boys playing near Knostrop Water Works. He was 5 feet 5 inches tall. This ‘hurricane’ weighed ten stone. Since his final release from High Royds psychiatric hospital in 1967 he had spent some time in prison in Leeds and Preston, and at the Church Army Hostel in The Calls in Leeds, but mostly he was sleeping rough. His West African friends who tried to help him when they ran into him said he was in a very bad way, not talking sense, laughing and looking over his shoulder all the time. The owner of a restaurant in the city centre said he looked ‘miserable and scruffy’ but he was a ‘harmless type of person, [maybe] a bit mental’.[2]

When his body was found, Police Cadet Gary Galvin immediately shared his thoughts that Ellerker and Kitching were involved in David’s death. Galvin was based in Millgarth police station, where Ellerker and Kitching were his seniors. Galvin had heard the stories of their brutality towards David. To its credit, Leeds police called in London’s Metropolitan force to investigate. It is hard to exaggerate Galvin’s bravery in blowing the whistle. So tyrannical was the Leeds police mentality at the time, a senior officer told me, that no police cadet was placed in Millgarth station for ten years after Galvin gave his ‘treacherous’ statement.

Leeds police was notorious for its corruption and racism. Ellerker had already been sentenced to jail and dismissed from the force in 1969 after he tried to cover up the death of an elderly pedestrian caused by a police car driven by two of his drunken seniors. Black people feared the police. Leeds’ United Caribbean Association told a parliamentary enquiry in 1971 that

Harassment, intimidation and wrongful arrest go on all the time . . . police boot and fist [black] youths into compelling them to give wrong statements . . . We believe that policemen have every black person under suspicion . . . and for that reason every black immigrant here in Leeds mistrusts the police.[3]

Gary Galvin’s concerns proved right. The court heard from other officers that Ellerker and Kitching had taken David out of Leeds and dumped him, telling him never to return. But he always did. So they put him in a dustbin and rolled him down the street. They set fire to the newspapers he slept on. They urinated on him as he lay on the ground, grabbed his hair and banged his head on the ground.

Phil Ratcliffe, then working in the central charge office at Millgarth, told the court: ‘I have never seen a man crying so much and never utter a sound’ as Kitching pushed his knee into David’s back at the charge counter. David, he said, was placid, far from violent, withdrawn and subdued. PC Hazel Ratcliffe testified that she had seen David kicked so hard in the groin while lying on the floor at Millgarth that he had been lifted off the ground. Even in those days, there were police officers who had the courage, and the ethics, to speak out.

Ellerker got three years in jail and Kitching 27 months, convicted only of actual bodily harm. Judge Hinchcliffe had told the jury they could not consider the manslaughter charge. He thus ruled out the evidence of George Condon, a bus conductor. Condon told the jury he had seen a scruffily-dressed man being pursued down an alley off The Calls, close to the River Aire, by two men in police uniform at about 5am on 18th April 1969.

The judge said this did not identify Oluwale, Ellerker or Kitching. Ellerker and Kitching were on duty, but remarkably, they had lost their note-books for that night. Over a thousand other officers were able to prove they were not in that part of Leeds at that time. Ellerker and Kitching came out of jail quite soon and got civilian jobs. They never answered any further questions.

Racism

Racism was not discussed in the court. It was later argued by one of their defence lawyers that Ellerker and Kitching were just the ‘night soil men’, obsessed with cleaning detritus off the streets of Leeds. But Perkins had found that in one of David’s charge sheets, against ‘Nationality’, the word ‘British’ had been scrubbed out and ‘Wog’ inserted. Gary Galvin told the enquiry that he thought David had been killed “because he was coloured and there is racial prejudice everywhere”, but that too did not reach the court.

British racism had been explained in 1956 in the daily News Chronicle by Tom Baistow in a four part investigation call ‘Colour Bar in Britain’. He reported on active prejudice in housing, employment and the trade unions. ‘In small numbers [‘coloured immigrants’] fit in, but it creates difficulties if too many come into the railways’ the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen told Baistow. ‘I don’t ask at white doors any more,’ was the headline for his housing report. (It is worth noting that Baistow met whites who were not prejudiced.)[4]

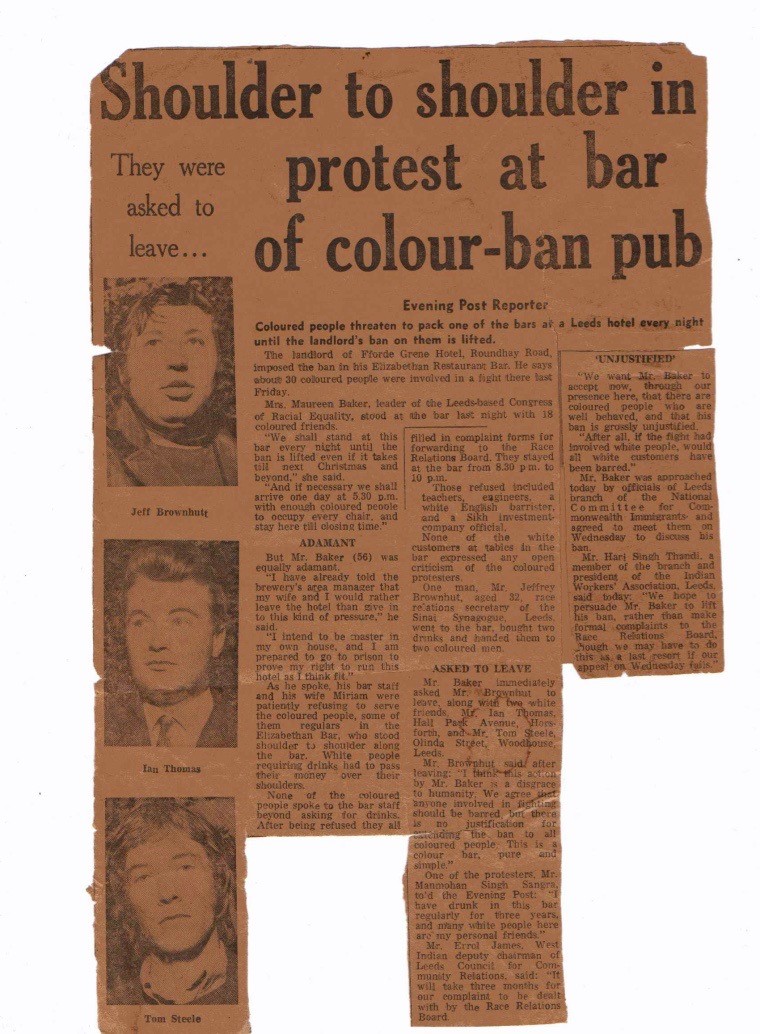

The United Caribbean Association had been campaigning against racism in Leeds since it started in 1964, and at least one of its actions, in conjunction with the Congress for Racial Equality, against a pub practising a colour bar, reached the newspapers in 1969 [cutting inserted below]

Racists attacked Asians in Leeds shortly after David Oluwale died. A small white gang set upon Bhupinder Singh and Dian Singh Ball and other Asians in the Burley area of Leeds, just north of the city centre, on 27th July 1969. One of them, Kenneth Horsfall, was killed. A few days later, somewhere between 800 and 1,000 white men and women surged into Hyde Park Road, attacking Asian-owned shops and setting fire to a car believed to be owned by a Pakistani. Humphry and John reported: ‘Nazi salutes were given and cries of “Sieg Heil” as scuffles between the police and the crowd broke out. Four policemen were hurt making twenty-three arrests.’[5]

Surveys around this time gave further facts. The most authoritative, by Policy and Economic Planning, reported in 1967.[6] It examined 500 potential discriminators (including employers, trade unions, housing providers, and services such as insurance companies) and showed that discrimination was demonstrated in 90% of the ‘situation tests’ they set up, with immigrants of African, Caribbean, South Asian, Cypriot and Hungarian origin. In an employment test, fifteen white English and ten white Hungarians were told there was a vacancy and they should apply, but only one ‘coloured immigrant’ got that response. Three out of four housing accommodation agencies were practising racial discrimination; two out of three estate agencies were doing the same. Another survey in north London in 1964 established that 49% of residents objected to having a black neighbour. 62% of people polled by the Institute of Race Relations justified their hostility with the (erroneous) argument that immigrants took more from the welfare services than they put in via taxation.[7]

So it is hard to accept that Ellerker and Kitching were just doing their job in keeping the streets of Leeds clean and orderly, irrespective of skin colour. They may have been, as described in court by Sgt Dougie Carter, ‘hard and ruthless and untiring’ in their harassment of rough sleepers, but none of them received David’s treatment. As we have seen, Kitching said David was an animal. After they dumped him in Middleton Woods, miles from the centre of Leeds, Kitching told his colleagues at Millgarth: ‘He should feel at home in the jungle’. Racism intersected with hard policing on David’s body.

Life, work and mental health

Between 1949 and 1953, David’s friends described him as happy; he was ‘always making jokes and could be the life of the party’, according to Abby Sowe. David delighted in the nickname Yankee (acquired due to his admiration for American popular culture). He dressed sharply and enjoyed dancing at the Mecca Ballroom in Leeds. It has been said that he had two children with a woman called Gladys; if that is true, there is no trace of them. But there was plenty of engagement with women, albeit with complications. David’s friend and fellow Nigerian Gabriel Adams (Gayb), told me that when the West African men went out dancing, to overcome resistance from the white men, they had to make an arrangement with the DJ to have an ‘invitation’ moment, when the black men could cut in and ask a woman to dance. This went well for Gayb, who soon got married. One of his daughters, he told me, became a manager at Harvey Nichols in Leeds.

All this complicated pleasure was being duly noted by the powers-that-be. Sheffield’s Chief Constable reported in 1952 to the government in London: ‘The West Africans are all out for a good time, spending money on quaint suits and flashy ornaments and visiting dance halls at every opportunity. The Jamaicans are somewhat similar, but they have a more sensible outlook and rarely get into trouble.’[8]

David had lots of jobs, doing the dirty work of reconstructing post-war Britain. He did manual work at Croft Engineering in Bradford. He was a hod carrier on a building site and he worked at the Public Abattoir and Wholesale Meat Market (next to Kirkgate Market) in Leeds. Then he did labouring work at Sheffield Gas Company. By autumn 1951 he was back in Leeds at the abattoir. Life was progressing as it did for most of the other Africans and African-Caribbeans in Leeds (there were only 985 of them in 1951): doing hard unskilled work, enjoying some entertainment and facing up to racism.

In April 1953 David was arrested after an altercation at the King Edward Hotel in the centre of Leeds. He was jailed for two months. In prison, it was said, he behaved strangely, and in June he was admitted to the psychiatric wing of St James Hospital. They referred him to Menston Asylum on the outskirts of Leeds. He was held there for the next eight years.

Was he correctly diagnosed? The psychiatrist described him as ‘apprehensive, noisy and frightened without cause . . . [he was] childish and wept when talking of his fears’. His medical records have disappeared so it is hard to be sure if this is real psychiatric illness; perhaps these are the understandable fears of a man who has already encountered the police and racist white men?

Violence was an ever-present threat for the West Africans in this period. Joe Okogba was warned by a Nigerian called Frank Morgan: ‘The white man — he want to fight you all the time’. Gayb told me that while most of the West Africans tried to avoid fighting, David would always stand up for himself. Another Nigerian friend of David’s who worked with him in Hadfield Steel Works in Sheffield (in 1951) told Caryl Phillips that ‘He wouldn’t let anything go . . . If a foreman said something wrong to him it would be “fuck off” . . . he was a stubborn, fighting man who simply found it impossible to back down and work the system’.[9]

Whether or not he was mentally ill in 1953, a diet of largactyl and electro shock therapy at Menston meant when, in 1961, David was pitched back on the streets he was in very bad shape. His friends described him as ‘gone’, nervous, twitchy, slow, shuffling, and laughing for no reason. In 1962 he got another six months in jail for biting the finger of the park ranger on Leeds’ Woodhouse Moor. From 1963 he slept rough, or squatted, or briefly found a place at the Faith Lodge hostel for the homeless.

In 1965 he was back in custody for maliciously wounding two policemen. In Armley jail Dr Carty, called in from High Royds Hospital (the new name for Menston Asylum), described him as overactive, garrulous, aggressive, ‘very paranoid about the police’ and hearing threatening voices, sometimes in Yoruba, sometimes in English. Carty concluded he was a ‘dullard’. David said he was a heavy drinker of sherry and rum. Of course, his encounters with the police might well have made him paranoid, but his symptoms are similar to those observed by his friends at this point, so he was, or had been made, mentally ill.

In court, Ellerker and Kitching’s defence counsel made much of David’s violent aggression. Gilbert Gray QC told the court ‘You would not bend over [in the hospital] because as quick as a flash and as lithesome as may be [David] would leap up like a miniature Mr Universe and have hold of you, scratching and biting with a mouthful of the biggest dirtiest teeth Mr Dent had ever seen in his life’. Mr Dent was a psychiatric nurse at High Royds who gave evidence.

But Kester Aspden unearthed other accounts which give a different picture. In 1970 Leroy Phillips was a psychiatric nurse at High Royds. He said that David could be a handful at times, but was no problem if properly dealt with. He believed that Eric Dent – ‘an old school charge nurse’ – had exaggerated the danger David posed. And David Odamo, a Nigerian who had worked as a psychiatric nurse at High Royds, wrote to the Leeds’ Chief Constable after reading press reports of the trial to say that David ‘was not a violent person’. On 27th April 1967, David was discharged from High Royds. Giving credibility to Phillips’ and Odamo’s descriptions, Dr Carty described him as quiet and co-operative, reporting that his hallucinations faded and his ‘persecutory ideas’ had mainly gone.

Evidence collected by Chief Superintendent Perkins and his team, found in the archives by Aspden, but never heard in court, corroborated a view of David as easy-going when treated properly. PC Michael Hargreaves told the investigation team that David ‘didn’t offer any objection’ when he asked him to move on. PC Peter Smith said: ‘He was never violent, he just picked his bag up and went away chuntering’. PC Barry Clay said ‘he went away without much trouble but used to jabber like a witch doctor’.

There is thus good reason to question not just the initial diagnosis of David’s mental health, but to suggest that racism played its part in the treatment David received in hospital and in the defence case in court. Dent’s portrait, embellished by Kitching’s QC, of David as a muscled fighter who used his fearsome teeth, reminds us that racism can be embodied, gendered and resorts to animal imagery.

But we should also note in David’s story that mental health, whatever your skin colour, is not to be simply pinned down. If a person was wrongly categorised in 1953, and incarcerated in an asylum, like so many people of all backgrounds were, their future was dire. It was not only black people ‘treated’ with drugs and shocks who found themselves discharged in the 1960s without proper support. So we should see David’s sorry tale as one where his ultimate abjection resulted from the interaction of several factors: police violence, racism, combined incarceration (prison and psychiatric hospital), homelessness and destitution. While enduring this multiple oppression, David, as we have seen, remained defiant and as dignified as he could be.

Remembering Oluwale in prose, poetry and more

The Yorkshire papers covered the trial in detail, and there was a pioneering article about David Oluwale in 1972 by the late Ron Phillips, a British-Guyanese activist and writer. A memorable radio play by Jeremy Sandford was broadcast by BBC Radio Brighton in the same year, and the script was published in 1974, but David Oluwale was mainly forgotten.

Most of Leeds’ black and Asian settlers had settled in Chapeltown. Lots of white people, like me, enjoyed living there too. Walking along Chapeltown Road in the 1970s, no-one could miss REMEMBER OLUWALE painted in large white letters on the grey Yorkshire stone wall near the Hayfield. I read Ron Phillips’ article when it came out and did a project with students at Jacob Kramer College of Art in 1975 using Phillips’ searing account, newspaper cuttings of the trial and Sandford’s play. At dusk in pouring rain we walked from Otley Chevin, where David had been dumped one night by Ellerker and Kitching, back to the city centre. He was remembered another ways too. Leeds United fans sang an anti-police song about David soon after the trial. The Jamaican-British poet Linton Kwesi Johnson produced work referring to David in the latter part of the 1970s.

But it wasn’t until Kester Aspden and Caryl Phillips produced their books about Oluwale in 2007 and 2008 that the story came to life again. These, and events organised by the Oluwale Memorial committee, inspired songs, poetry (notably by Ian Duhig), a new play (by Oladipo Agboluaje), a short film (by Corinne Silva) and a lot of journalism.

I have written about this historical and creative work in detail elsewhere, pointing to the disparities in the various ways David’s story has been told, with particular reference to the work which states that Ellerker and Kitching killed David, and those that follow Judge Hinchcliffe’s direction.[10] Memory, as that article says, is a trickster; it’s important to recognize that academic work also relies on memory and while it strives to carefully balance the evidence, it also reflects its authors’ value standpoints and ideologies. Hence any work on David’s life, in the creative arts or in university departments, will always be contentious.

The David Oluwale Memorial Association

A memorial to David was suggested by Caryl Phillips when he spoke about his research at an event at Leeds Metropolitan University (now Leeds Beckett University) in 2006. Phillips was born in St Kitts but grew up in Leeds. He is now a writer and a Professor of English at Yale in the USA. His formative years, however, were marked by Oluwale’s presence and death, and his long essay Northern Lights starts with imagining a black girl encountering David on Chapeltown Road.[11] The David Oluwale Memorial Association (DOMA) started life as a committee based in Community Partnerships and Volunteering at Leeds Met. I convened that committee, and later helped set up the DOMA charity, registered in 2012.[12]

The Remember Oluwale charity aims to improve diversity, equality and social justice in the city of Leeds by both reminding the city of the grim history it has to come to terms with, and by educating and campaigning for change today in all the afflictions David endured. We are particularly concerned with the plight of those seeking refuge in the UK today, with people whose mental health is challenged, with the homeless and destitute, and with victims of police malpractice. Some of those people are black, and we focus on racism in all its manifestations.

DOMA’s vision is positive. We commend the improvements that Britain has made since David’s day and we especially note Leeds City Council’s commitment to making Leeds a more equal, more welcoming and more hospitable city. We are dedicated to bringing the marginalized and excluded into the centre of the city and its social and cultural life. We invariably include the creative arts in our educational and campaigning work, and everything we do relies on partnerships arrangements. We ensure the voices of ‘experts by experience’ are heard. Our Partnership Symposium, held at Leeds Beckett University courtesy of its social science research group, was a good example of this. Another event, led by the School of English at Leeds University, featured contributions from the writers Gary Younge and Caryl Phillips as well as several academics and the poet Zena Edwards.

The Leeds group Royal Blood, performing at the Oluwale Partnership Symposium,

Leeds Beckett University, 17.04.15 [Photo: Max Farrar]

A recent venture, with the Big BookEnd Festival and Fictions of Every Kind, was a poetry and short story competition, judged by Caryl Phillips, Marina Lewycka and Ian Duhig. Attracting 70 contributions, the published Anthology included the 26 entries in the long list, along with already published work relating to David’s life by Kester Aspden, The Baggage Handlers, Ian Duhig, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Steve Lunn, Sai Murray, Zodwa Nyoni and Caryl Phillips.[13]

Our flagship project is the creation of a memorial garden close to the River Aire at the point where David was last seen, near the Leeds Bridge. We are negotiating with Asda for the lease of a small patch of their land to create David’s Kitchen Garden. This will be a space, welcoming to all, where we can eat, talk and experience poetry, film and music. We have already used this derelict land for our launch event on a freezing night with performances by Leeds Young Authors (facilitated by Khadija Ibrahiim) and The Baggage Handlers (facilitated by Rommi Smith) and Corinne Silva’s film ‘Wandering Abroad’ was shown.

Working with The Tetley Centre for Contemporary Art and Education, we are now commissioning a world-famous artist to build a garden sculpture in memory of David. This will help bring his story to a much wider audience and provide further space for reflection and become a platform for social progress.

David Oluwale is not to be one of those working class people who are ‘hidden from history’. He is to be remembered as both victim and agent, a man who struggled perpetually against insuperable odds to make a good life as a migrant to Britain.

Max Farrar’s PhD thesis on black-led social movements in Chapeltown, Leeds, was published as The Struggle for ’Community’ (Edwin Mellen, 2002). Since retiring in 2009 he spends his time with family and friends, writing, taking photos, doing politics, and working as secretary to the David Oluwale Memorial Association. More at www.maxfarrar.org.uk or www.rememberoluwale.org

Notes

[1] See Tony Kushner (2012) The Battle of Britishness - Migrant Journeys 1685 to the Present, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

[2] Unless otherwise attributed, all the direct quotes, and many of the facts in this article come from Kester Aspden (2008) The Hounding of David Oluwale, London: Vintage.

[3] House of Commons Select Committee on Race and Immigration 1971-2 Report on Police-Immigrant Relations, HC-1, HMSO, cited in Max Farrar (2002) The Struggle for Community Lampeter and New York: Edwin Mellen Press, p. 221. The latter is a very detailed sociological study of black-led social movements in Chapeltown, Leeds, UK, from the 1960s to the 1990s.

[4] Tom Baistow (1956) ‘Colour Bar Britain’, a four part series in the News Chronicle, 8-11 October 1956

[5] Derek Humphry and Gus John (1972) Because They’re Black, Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, p. 151

[6] The Policy and Economic Planning group report was published as W W Daniel (1968) Racial Discrimination in England, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

[7] See Dilip Hiro (1973) Black British, White British, Harmondsworth: Pelican Books

[8] Carter, Bob; Harris, Clive; and Joshi, Shirley (1987) The 1951-5 Conservative Government and the Racialisation of Black Immigration, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick, Policy Paper No. 11, October 1987. Available at https://web.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/CRER_RC/publications/pdfs/Policy%20Papers%20in%20Ethnic%20Relations/PolicyP%20No.11.pdf

[9] See the chapter on Oluwale titled ‘Northern Lights’ in Caryl Phillips (2007) Foreigners - Three English Lives, London: Harwill Secker.

[10] Max Farrar (2015) ‘Remembering Oluwale: Re-presenting the life and death in Leeds, UK, of a destitute Nigerian’. Available at http://www.rememberoluwale.org/david-oluwale/remembering-david-in-history-poetry-music-and-film/

[11] ‘Northern Lights’ in Caryl Phillips (2007) Foreigners - Three English Lives, London: Harwill Secker.

[12] DOMA is on the web at rememberoluwale.org and on Facebook and Twitter as RememberOluwale

[13] SJ Bradley (ed.) Remembering Oluwale — An Anthology, Scarborough: Valley Press valleypressuk.com

[Published in Leeds African Studies Bulletin 78 (Winter 2016/17), pp. 172-185]