From the South to the North: Image of a Circular Economy. An Interview with Andrew Esiebo

By Xavier Moyet

This guy changes the narrative of these clothes sent to Africa “to help”, as with his skills he repurposes them and gives them a second life. It is viable because it is transformational: ecological and economical. ... I see this story as a metaphor for what we can do, and dwell into our “disadvantage” and turn it into an advantage.

Introduction

Andrew Esiebo is an award-winning Nigerian artist and a visual storyteller who through his work seeks to chronicle the rapid development of urban Nigeria as well as the country's rich culture and heritage. He was recently involved in a photography project, titled From Second Hand in Lome to Second Life in Paris. This project focuses on the Togolese designer and stylist Amah Ayivi, who re-uses second-hand clothes that originally come from Europe and North America as charity; he ships them to Paris where he curates and sells them as chic vintage clothing. Andrew documented this example of a North-South-North circular economy in his photography project. In this interview, conducted on 10 January 2021, he elaborates on this work. The interview is presented with a selection of photos that Andrew produced. The selection is based on the entanglement with other sociological themes. All photographic credits are Andrew's.

This interview was generated through an iterative process: after conducting the interview, it was transcribed by myself, and then passed two rounds of editing by Andrew and myself respectively. The interview, in which Andrew elaborates on his work, is a practical instance of the “co-construction” of ethnographic knowledge between Andrew and myself as interviewer cum anthropologist. Concretely, the interpretations derived from the ethnographic observation are arising from a shared cognitive process, coming from a discussion. This collective process challenges the classical and somewhat problematic division of anthropological knowledge production between “researcher” and “informant”, a division also infused with an implicit power relation. Furthermore, we hope that the ethnographic content will be enhanced by the visual and artistic dimension of this work. As Andrew puts it later in this interview, using pictures can elevate the experience.

Interview

XM: Thanks for this interview, Andrew, can you present yourself, please?

AE: My name is Andrew Esiebo, based in Nigeria but working across Africa, Europe and beyond. I am a storyteller. I am very keen to use visual materials to tell stories. My activity is not only about taking pictures but about revealing the layers in an image.

XM: About the series “Second-hand clothes”, how did you find the topic?

AE: My projects usually start from little ideas, from things I observe around me; these observations and ideas then gradually develop into projects. The inspirations for the ideas could come from personal encounters, or when I am on an assignment, commission… The “From second hand in Lome to second life in Paris” series came about when I was commissioned by a French Magazine (Le Monde), to go to Togo and do a report on a Togolese Paris-based stylist called Amah Ayivi. From Paris, he goes back to Lome (Togo), buys second-hand clothes coming from the West and brings them back to France as vintage style.

I was really intrigued by his story. While I was there, I was so blown away by Amah’s dexterity, his skills in selecting the clothes, repurposing the clothes. I knew the story would be incomplete if I would not continue his story in France. I was really keen to see how this guy distributes the clothes, how he gives them a second life, so, I took it upon myself to go to France. This guy changes the narrative of these clothes sent to Africa “to help”, as with his skills he repurposes them and gives them a second life. It is viable because it is transformational: ecological and economical. This inspired me to develop the assignment into a project.

XM: So, you invested yourself for the second part of the report in Paris. That was more your own curiosity?

EA: I approached other media, like New-York Times (NYT), they liked the idea but were hesitant to support the project. I was really determined that if they don’t support me, I will go with my own means. Which I did and, along the way, NYT supported me with a substantial part of the cost, at least. I went to Lome twice. I worked with a writer (Allyn Gaestel), to bring her own point of view to the story.

It was quite a successful project. It got published in different places and exhibited at the Breda Photo Festival in the Netherlands. It is not just the pictures, but the process, the ingenuity of this guy, I find the story inspiring as an African, even if we might be in a deprived situation, we can always find a way to appropriate a situation and take advantage of it, to use it to turn lemon to lemonade. I see this story as a metaphor for what we can do, and dwell into our “disadvantage” and turn it into an advantage; he has done this and even gone beyond that.

XM: What is the work of Amah Ayivi?

EA: The way he collects his material is very sophisticated and sensitive; paying attention to details, like the clothes production year, sorting out fake and original. If you are not very smart, you may end-up having fake vintage. But what I like about him is that he is not only buying second-hand clothes but also giving them a new purpose. They reflect a kind of African Urban Culture. Some of the designs he makes, reflect the styling of Sankara for instance, he would look at the way Sankara would dress in this era and would connect his clothes with it, it almost reflects the style of this period, or the style of clothing during the era of Malik Sidibé.

He uses his clothes to reflect African urban lifestyles. Lately, he has been doing some kind of fusion, using African traditional attires, mixing them with second-hand clothes, so I like this sensitivity. I remember I spoke with him about what really inspires him, and pictures of Sidibé inspire him. His image has some Pan-African style in them, they are a statement in themselves, making us bold, proud. It was the new African era where things were coming-up new, I think that’s what I love about his work, it is not only about fashion, it has a cultural and conscious message.

Photos

Now, let’s present a selection of the pictures, to show the way in which Amah works, and to illustrate his ideas regarding circular economy, the positive attitude, the ecological dimension and the fusion.

Figure 1: Hand with silver rings on green shirt. © Andrew Esiebo

Figure 2: Indoor and outdoor clothes markets in Lome. © Andrew Esiebo

One can see the market with, on the side, the indoor market (in huge solid infrastructures), and outdoor markets, made of makeshift, in the background. This outdoor market is largely controlled by Nigerians. It has to do with the regulations imposed by the Nigerian state. Because of them, many traders moved to Togo to avoid the ban placed of 2nd hand clothes.

On the next image, we can see second-hand shoes. The second-hand industry is a very controversial topic: on the one hand, some people think it’s negatively affecting the growth local textile and clothing industries, but on the other, you can imagine the waste it would be if people were not to use those 2nd hand clothes again. Imagine the ecological consequences. On the image, we can only see a tiny fraction, if you cannot recycle things, it is going to be massive pollution for the environment. So, the purpose of the image was also to make you reflect on this over-consummation:

Figure 3: The ecological dimension of the 2nd hand market. © Andrew Esiebo

Out of this abundance, Amah carefully hand-picked a pair of shoes:

4. Hand-picked pair of shoes © Andrew Esiebo

Amah in Europe, walks in Paris urban space, close to Bastille.

Figure 5: Shoes "recycled" in Paris. © Andrew Esiebo

Figure 6: Amah in Paris. © Andrew Esiebo

Positive attitudes

Amah's vintage creation addresses the taste of well-off people living in the African diaspora, giving life to the African urban culture referred to before. On the one hand, they are happy to wear some exclusive clothe, that they are not likely to see, à l’identique, on other people. On the other hand, they are also keen to patronize a concept that is ecological, re-purposing purposefully 'used' clothe. They patronize the creator even more willingly since their act of consummation can also be embedded in a positive, and distinctively African fashion. They got style, and their allure is a silent discourse, a statement about their identity:

Figure 7: Amah’s customers. © Andrew Esiebo

Figure 8: Hypes people in the photo studio © Andrew Esiebo

Fusion

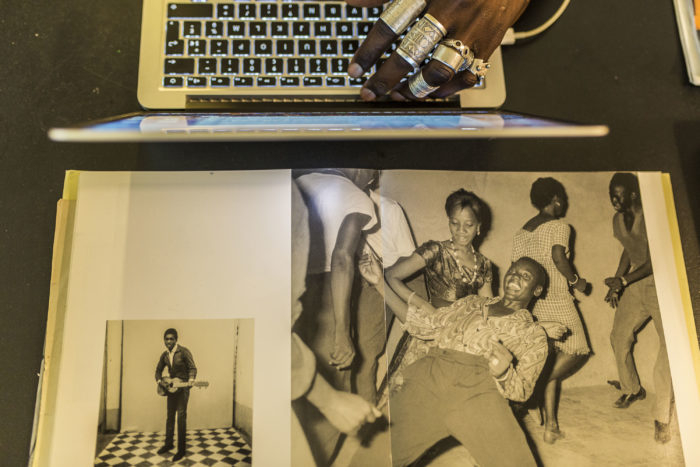

Figure 9: Styled hand, Mac computer and Sidibe's pictures. © Andrew Esiebo

Figure 10: Mixing traditional attires (Batakari) and the best of electro culture. © Andrew Esiebo

XM: Thanks for this showcase, Andrew. Once again, only a fraction of your series is presented here (link to the full series of photographs). Now, could you tell me how this set of photographs compares with other projects you have carried out?

AE: In a sense, some project can take more time to come to fruition, some may be right on the spot, an example is this project, compared with the project about Barbers in West Africa where I spent several years developing and executing the idea into a project.

XM: What about collaboration with researchers?

AE: My own work is inspired by my daily life experiences. I am a big fan of finding how a subject matters and relates to me. Of course, in some projects, you are asked to do it, you get sort of guidelines… but I like to work with researchers, like the project I did about Pentecostal churches with Annalisa Butticci. It was a rewarding experience because we worked really close, and I was able to learn more about the scientific implication of what I am doing and use that to improve my photography. What also helped is that our languages complement each other: she had a scientific language, and I have the visual language, and both help to communicate with people.

It was quite intense. I think the way artist think is different from a lot of academics, they make a lot of references, to theories, and blah blah… I get the impression that academics always have a position towards the thing they do, meaning that have a clear agenda, they have a reference, a theory. Coming from an artistical point, I have this free mind to explore with no limitations (…).

But we almost do the same thing, an anthropologist needs to be in the field to observe and make his own comments; likewise, to be a good photographer and storyteller, you must be a good observer, and use your visual language to make commentaries about what you have seen. The difference is that your observation has to be backed-up by theories and references, whereas for me, I have the freedom to express my own point of view, which I find more effective because it relates very well to the mass audiences.

I am using a visual language that is a mass language, it doesn’t have jargons, it is easy to connect to; while to relate to academic messages may be boring sometime, for instance, how can one describe a spiritual deliverance session in a Pentecostal setting with words for a person to feel? But as a storyteller using video, the sound, pictures, I will elevate that experience, such as in my series “Crazy World, Crazy Faith”.

We have similarities in our fieldwork, we have different ways to express it.