Combining Old Values with New: The Breakdown of Political Relationships in Colonial Bunyoro, Uganda

By Kerry Pearson

This article is based on the dissertation titled “Combining Old Values with New: The Breakdown of Political Relationships in Colonial Bunyoro, Uganda”, with which Kerry Pearson completed her BA in History at the University of Leeds. Together with Maya Aziz, she was awarded the 2022 Lionel Cliffe Prize for the best undergraduate dissertation on a topic relevant to African Studies at the University of Leeds.

Introduction

In 1962, Joseph Kalisa, President of the Democratic Party in Bunyoro, said that ‘Uganda people are likened to clay in the hands of a potter whereby the pot would crack or even break if ill-moulded’.[2] The region, or ‘clay’, had been moulded by the British Empire, the ‘potter’, from 1894 to 1962, during which time ethnic groups were fused, land systems were reformed, and the region’s economy was monetarised. And yet, the ‘pot’, now modern-day Uganda, had been moulded without care or thought for borders, indigenous values like kinship, or institutions based on communalism. Kalisa’s comment was part of the Lost Counties campaign which sought to return territory that Bunyoro had lost at the start of the colonial period; speaking in the 1960s, his idiom would have particularly resonated with those people of Uganda who still constructed ceramic vessels out of clay, which have been described as the proud ‘provinces of men’ in Bunyoro.[3] The vessels created were thin and fragile, similar to the conditions of a newly independent state. This article will therefore analyse how political identities and relationships in Bunyoro were refashioned and structurally weakened under colonial rule.

Bunyoro, inhabited by the ‘Banyoro’ people, is an interlacustrine kingdom located near Lake Albert, often remembered for its pre-colonial geographical vastness and political superiority.[4] Since the mid-nineteenth century, Bunyoro’s neighbours, the ‘Baganda’ people in Buganda, were a constant source of competition and the two kingdoms regularly raided each other’s territory.[5] Buganda was the first region visited by explorers and ‘proto-imperialists’, John Hanning Speke and James Grant, who, impressed by this meritocratic, centralised polity, quickly formed close relations with the Baganda.[6] Before reaching Bunyoro, British explorers had been fed negative, condemnatory images of the Banyoro as violent and regressive; thus when the British Empire embarked upon creating a Protectorate in the region, the potential ally for indirect rule was clear: Buganda.[7] In 1900, the partnership between Buganda and Britain was formalised with the Buganda Agreement, which not only strengthened the Baganda’s superiority in the region, but reinforced Bunyoro’s position as a conquered kingdom.[8] That same year, in accordance with the agreement, a proportion of Bunyoro’s territory was annexed to Buganda; this area became known as the ‘Lost Counties’.[9]

Although Bunyoro’s history is declensionist, historians must not ‘read history backwards’. Christopher Wrigley points out that ‘no African state is a smoothly functioning democracy, but collapse into tyranny, anarchy and civil war is not the norm’.[10] This article therefore aims to explore the reasons for the abnormal fracturing of political relationships and the demise of pre-existing political relationships both within Bunyoro, and between Bunyoro and Buganda.

More specifically, this article analyses how political relationships between the Banyoro and Baganda were undermined by the Lost Counties dispute, in which five and a half counties were given to the latter by the British.[11] The dispute was significant for several reasons. Forced assimilation of the Banyoro inhabitants of the Lost Counties into Buganda’s society meant that their connection to their history was fractured. Consequently, historical narratives were re-constructed by the Banyoro to legitimise their claim to the counties. Such nostalgia, or obsession with the past, led to heightened local ethnic nationalism which prevented cohesion between rival groups like the Banyoro and Baganda, meaning that chaos and instability in the post-colonial state became almost inevitable. Shane Doyle epitomises this idea, maintaining that a ‘fixation with the past in Bunyoro may have obstructed modernisation’.[12]

The Lost Counties dispute fundamentally reshaped modern Uganda. The crisis of political legitimacy and the tensions between central government and the kingdoms which it provoked, led directly to the deposition of Uganda’s head of state and the suspension of the country’s first constitution in 1966, and the abolition of monarchical governance in 1967.

Literature Review

Ugandan history can be characterised by the conflict between Buganda and Bunyoro, whereby the former kingdom was favoured by the British Empire, often working together to weaken Bunyoro. Scholarship has therefore tended to focus on Buganda at the expense of Bunyoro.[13]

This article provides a much-needed re-focus on Bunyoro’s political history, playing closer attention to African agency. Espeland’s notion of ‘politics of belonging’, namely the importance of belonging to a historically-related group, is influential.[14] ‘Politics of belonging’ is contingent on a group’s ability to voice their grievances and receive fair representation in politics, both of which are prerequisites for national stability.[15] Understanding how the Banyoro perceived themselves is critical to this work. Beattie writes: ‘How an African people regard themselves and their country after over half a century of British administration is a matter of importance’.[16] Although Beattie offers an invaluable insight into Nyoro customs, his suggestion that the Banyoro only understood themselves in the context of ‘Nyoro-European relations’, is limited. [17] In reality, relations between the Baganda and Banyoro, and the kingdom’s internal relations, were equally as important to their identity.

The historiography recognises that the Lost Counties caused colonial and post-colonial issues for Uganda.[18] Kiwanuka, former Professor of History at Kampala’s Makerere University and a staunch Buganda patriot, argues that ‘social discrimination’ against the Banyoro in the Lost Counties was the main cause of discontent in cross-kingdom relations.[19] More convincing, however, is Hall’s argument that Buganda sub-imperialism paved the way for a ‘Nyoro consciousness’.[20] This article will spotlight the forced assimilation of the Banyoro into Buganda’s unfamiliar culture, leading to structural injustices which initially undermined and subsequently sharpened Banyoro’s ethnic identity.

The historian Andrew Roberts suggests that there were no ‘formal complaints’ from the Banyoro in 1900 (when the counties were formally transferred), and that the British were ‘sympathetic’ to the campaign for the return of the counties.[21] However, oral primary sources demonstrate how Lost Counties residents had very little conception of democratic ideals and were thus unaware of their right to protest.[22] Juma Anthony Okuku, former lecturer at Makerere University, argues that although ethnic consciousness poses challenges to nationhood, the solution is ‘more… democratisation’.[23] However, liberal democracy, grounded in Western history and culture, was not culturally aligned with Bunyoro, where ‘popular representation’ was incongruous with Bunyoro’s historic practice of chiefs making authoritative decisions, and where representatives were not chosen by the people but by headmen.[24]

While the Lost Counties dispute is the prominent focus of this article, political relationships in Bunyoro cannot be understood without analysing land reform. The British decision to abolish bibanja land (land gifted by the king to informal chiefs), led to an erosion of the mutual chief-subject relations; unlike in the past, the two actors no longer depended on one another for security or prestige. Chiefs became civil servants as their positions were based less on ‘kinship and ritual’, and more on commodities and taxes.[25] Further to this, the refusal of the British to grant Bunyoro mailo (freehold) land, despite consistently promising it, had consequences for economic growth in the kingdom, contributing to a lack of trust between the Banyoro and Protectorate government. The Banyoro believed that they had been poorly treated because Baganda chiefs received mailo and thus enjoyed economic security and wealth from rent that was collected.[26]

The economic changes that accompany land reform were also significant to the breakdown of political relationships in Bunyoro, a kingdom with an ‘economy of affection’, where kinship, not money, was the ultimate goal.[27] Monetarising chieftaincy reduced the mutual dependency between chiefs and subjects because the former no longer depended on tenants’ busulu (tribute paid by tenants) or labour, but were instead paid by the central government.[28] The imposition of taxes – which were incongruous with Bunyoro’s communal gift-giving customs – led to an avoidance of paying taxes.[29] Communalism was also erased by the introduction by the British of cash crops, which, Peter Geschiere convincingly writes, led to haggling, creating a gap between the rich and poor.[30] Furthermore, Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, notes that such ‘capitalist liberalism’ threatened bonds between humans because they ‘pursue[d] their personal satisfactions’.[31]

A note on the sources

The historical re-focus within this article is hinged upon documentary analysis of a plethora of primary sources, enabling a well-founded study of Bunyoro’s political history. Most primary sources regarding Uganda are dominated by British accounts from explorers, missionaries, colonial officials, as well as the Baganda, who became literate before the Banyoro, thus enabling them to construct a written version of the kingdom’s history from early on. Such sources offer valuable insight into official policy and reforms but are limited due to their inability to articulate Banyoro perspectives.[32]

It is hoped that an examination of the few available first-hand accounts from the Banyoro render the article more nuanced. An inter-conversational approach will highlight the differences between sources; for example, official colonial reports on the Lost Counties differ greatly from more personal and emotional narratives that emerge from interviews between the Banyoro and the lawyers who represented them during the royal commission enquiry of the late colonial period. This approach exposes the rationale and motivations of certain authors.

True of all primary sources, oral testimonies and interviews must be read carefully due to the construction of a narrative. However, unconventional approaches are often useful, and this article emphasizes Alessandro Portelli’s argument that ‘oral sources are credible but with a different credibility’.[33] If oral histories are read and interpreted differently to written sources, they become invaluable, as they explain not the factual order of events, but the meaning of events, as well as the attitudes and memories of people involved.

The ‘Lost Counties’ Dispute

‘Whoever heard of a parent being ruled by his children?’[34]

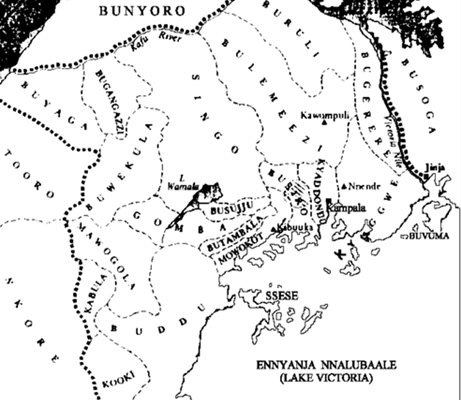

On 17 January 1962, nine months before Ugandan independence, John Beattie told the Molson Commission enquiring about the Lost Counties, that the Banyoro were known to ask: ‘whoever heard of a parent being ruled by his children?’[35] Pride and patriotism within Bunyoro were leveraged around the antiquity of the kingdom; its people described Buganda, the younger kingdom, as an offshoot or their ‘child’. Thus, in 1894, when the leader of the British mission to Uganda, Colonel Colvile, announced the annexation of five and a half of Bunyoro’s counties – Buyaga, Bugangazzi, Bugerere, Buruli, Buwekula, and northern Singo (see Figure 1.1) – to their neighbouring enemy, Buganda, there was an uproar amongst the Banyoro.[36]

Annexation was confirmed by the 1900 Buganda Agreement, despite no consultation with the Banyoro, with several high-ranking Banyoro later claiming: ‘Neither were we present, nor represented at… the negotiation of the 1900 Agreement… We merely woke up one morning to find that… five and a half of our original counties had been alienated from us overnight.’[37]

Figure 1.1 – Bunyoro’s Lost Counties (Buyaga, Bugangazzi, Buwekula, Northern Singo, Buruli) annexed to Buganda in 1900[38]

Bunyoro was a conquered and now dismembered kingdom, having serious consequences for political stability in the region and nation state.[39] The dispute was significant for three reasons. Firstly, the Banyoro’s strong political and ethnic identity was rendered fragile by Buganda sub-imperialism. Secondly, the dispute rocked any trace of representative stability as Banyoro were misrepresented and neglected from political office. And finally, the tactics of the Mubende Bunyoro Committee [MBC], a patriotic lobbying group, namely their emphasis on pre-colonial greatness, caused challenges for cross-border relations between the two kingdoms.

Ethnic identity in the Lost Counties

Ethnicity is a closely studied theme in African history and can be understood as a formation of identity between a group which shares history, culture, language, and customs. Historically, ethnicity has been constructed by colonists and sub-imperialists to achieve an ulterior motive; the Baganda in the Lost Counties were determined to expand their territorial power and increase their population to ensure larger influence in Protectorate affairs.[40] Over time, they resolved to retain their enlarged territory and population to maximise their representation in national politics. The political construction of ethnicity and the merging of different groups had severe consequences for political relationships.[41]

Clifford Geertz highlights that within ethnic communities, ‘the one aim is to be noticed, it is a search for an identity, and a demand that that identity be publicly acknowledged’.[42] Buganda sub-imperialism in the Lost Counties meant that not only was the Banyoro’s identity not ‘publicly acknowledged’, but they were deliberately neglected. Hall defines sub-imperialism, or internal colonialism as having a core (Buganda) and a periphery (Bunyoro), whereby the latter is prohibited from engaging in the political sphere.[43] Alienation from the political sphere was reinforced by the British implementation of Baganda chiefs, or ‘subordinate administrators’ in the counties.[44] The Banyoro provided labour and taxes to these administrators, arguably undermining their autonomy on their own land, leading to a ‘departicipation’ in politics and strengthening of local nationalism.[45]

Local nationalisms, Kiwanuka convincingly notes, are often neglected in ‘Western historiography’.[46] However, his claim that there were only three major nationalisms - Ugandan, Kiganda, and anti-Kiganda, does not accurately describe Bunyoro’s sentiments. [47] A ‘Nyoro consciousness’ emerged that not only opposed Buganda and British rule, but that sought to reassert and salvage Bunyoro’s culture and thus pre-colonial greatness.[48] Thus, Ambedkar’s argument that there is often a strong ‘longing not to belong to any other group’ is credible[49]. The Banyoro’s heightened ethnic nationalism clashed with both Buganda and Ugandan nationalism, meaning post-colonial politics were ‘tinged with ethnic loyalties’, having detrimental impacts for national cohesion.[50] Milton Obote declared after independence: ‘The tribe has served our people as a basic political unit very well in the past. But now the problem of people putting the tribe above national consciousness is… an issue we must destroy.’[51]

Ethnicity, however, is not static, and the strength of identity is not equal across regions. Cultural assimilation into Buganda had varying success rates.[52] Central counties like Buyaga and Bugangazzi, which represented the highest ‘pre-colonial status’ of the kingdom because of their holding of former mukamas’ [kings’] tombs, were staunchly opposed to assimilation.[53] On the other hand, in peripheral counties like Buwekula, it was suggested by the Baganda-dominated Saza (county) council with little public opposition that the area had always been part of Buganda; members asserted that no Buwekula ruler had been a Munyoro, and that there had never ‘been a battle whereby the Baganda conquered Buwekula’.[54] They opposed the work of the MBC, who they claimed had ‘the purpose of taking us to a different kingdom to make us serfs’.[55] Petitions and protests from Buwekula were rare, compared to those sent from Buyaga and Bugangazzi. Because Banyoro discontent was not universal, political relationships amongst the group were fractured, as there was heightened disunity and conflict over who belonged to the kingdom.

Language is important within ethnic identity. Runyoro and Luganda differ; nineteenth-century explorer, James Grant, noted that ‘the language of [B]Unyoro, as spoken by its natives… had not the mumbling sounds of the Uganda dialect’.[56] And yet, despite this difference, Runyoro was banned in public institutions and the Banyoro were forced to speak Luganda. In 1962, an informant, Laboni Musoke, recalled when an old woman, Byengenzi, was imprisoned for a fortnight and fined seventy-five shillings for speaking Runyoro in a court; he said that she was ‘unjustly and intentionally made to suffer for nothing’. [57] The Governor’s deputy remarked that the main grievances amongst the Banyoro were that in being ‘forced to speak an alien language’, they were growing apart from their culture, thus reiterating the demise of Bunyoro’s connection to their culture, history, and politics.[58]

An anecdote from the colonial official Mr Dunbar in 1962 also sheds light on the suppression of Runyoro and the apprehension of many Banyoro. Dunbar’s car tyre had a puncture, and when a group of people approached, offering their support, they greeted Dunbar with ‘Wasuze Otyano’, the classic Luganda greeting.[59] Dunbar, recognizing that the group were not Baganda, addressed the group in Runyoro. He later told the court that the people were from Buruli: ‘I said to them ‘why do you talk or greet me in Luganda’ and they said that ‘that is what we say at first but obviously you know we are different people. Therefore, we are talking to you in a language that you understood and we understood’.’[60]

Primary sources on the Lost Counties dispute are largely comprised of oral interviews and testimonies such as Dunbar’s.[61] There are, as with all sources, limitations to this approach. Accounts are reliant on memory and accuracy; both Musoke’s and Dunbar’s narratives are likely clouded by their bias towards the ethnic group, while accounts from the Banyoro, such as those in Buruli, may have been overshadowed by fear of punishment. Oral interviews during the campaign to return the Lost Counties may also be limited due to the lawyers’ choice of questions in order to extract a certain narrative. However, these sources remind historians that the issue was not necessarily whether the Banyoro were discriminated against in the Lost Counties, but that the group had strong sentiments of alienation. As Portelli argues, ‘oral sources tell us not just what people did, but what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did’; this is true of the Banyoro in the counties, who perceived the British and Baganda actions as unjust and oppressive, leading to their construction of politically-motivated narratives.[62]

In his rough notes for the judicial case for the return of the Lost Counties, Foster, leading lawyer on the case, poignantly explained why bias and exaggeration within accounts were arguably insignificant to the campaign: ‘Even if the government of Bunyoro were unable to establish even a single clear case of discrimination, it would still remain true, first that the Banyoro feel that there has been discrimination, and secondly that discrimination is not really the cardinal issue.’[63]

Evidencing Portelli’s argument is the fact that the MBC believed, or claimed to believe, that the British, although formerly abolishing slavery, were allowing the Banyoro to be treated like serfs as their institutions and values were erased by Baganda. This campaign strategy attracted widespread attention and was partially successful in the later return of two counties.[64] They said: ‘We need hardly mention the fact that, whereas there are many and diverse races… within the Commonwealth, Great Britain has never been known to interfere with their individual customs and tribal usages, such has been and is still the case by the Baganda towards us.’[65]

The suppression of native language had critical consequences for personal identity because Banyoro had to change their names and give their children Kiganda names.[66] An empirical evaluation of censuses is a valuable, quantitative way to understand forced ethnic change, and Uganda’s 1948 and 1959 censuses were suspect in their reliability. Although D.A Lury, a government statistician in charge of the 1959 census, said that there was no reason to question the accuracy of the results, suggesting that large numbers of Baganda recorded in the Lost Counties could be accounted for by migration, he failed to address the intimidation Banyoro had been subjected to by Buganda’s enumerators.[67] For example, a Munyoro, Mr Rwamanika, told the court that seventeen members of his family were wrongly recorded as Baganda instead of Banyoro: ‘When I said that… I was Munyoro, I was told that… I must say I was Muganda.’[68] Lury also did not recognise the critical point that the Banyoro were less educated than the Baganda, meaning that enumerators were able to ‘assist’ them when recording their ethnic identity.[69] For example, the changing of names enabled enumerators to make comments such as: ‘that is [a] Kiganda [name]; you are not Munyoro’.[70] Ultimately, the Banyoro had little authority over their recording.

Censuses are fundamental to a state’s (and kingdom’s) formulation of policies, strategic planning, and thus representative democracy. The inaccuracy of Buganda’s census had consequences for post-independence stability because Banyoro were not truly represented in the construction of constituencies; they lacked not only a sense of belonging, but their fair share of resources too.[71]

Dependency theory can be adapted to analyse this unfair distribution of resources in the Lost Counties. The theory first emerged in the 1950s as a way of explaining why former colonies remained poor and tied to their former metropoles, and its proponents contend that the world’s central states developed at the expense of peripheral states. [72] However, the theory also offers an interesting explanation for uneven regional development within Uganda. The British colonial state consciously categorised regions like Buganda as ‘core’, bestowing them with strong levels of investment, and others as ‘periphery’, where wealth was lacking.[73]

Even more specifically, within the Lost Counties, often absentee Buganda mailo landlords benefited from Banyoro’s labour and poll taxes; members of the MBC proclaimed that money from luwalo (labour) taxes were paying for ‘foreign, native rulers… [and their] personal emoluments, at our own expense’.[74] The organization claimed that the Banyoro had been rendered a ‘source of wealth to the Baganda which flows continually into their purses’, metaphorically describing the movement of Bunyoro’s resources into the hands of Buganda’s government.[75]

A critical question must therefore be asked: how did the Banyoro understand democracy? Musehemeza makes a convincing argument that African participation in politics is linked to their perception of resource gain; when the Banyoro lost resources at the expense of the Baganda, they became disillusioned with democracy and the nation state; cross-kingdom political relationships thus began to decline.[76]

Representation and democracy

Governor Crawford feared that if the Lost Counties dispute was not solved by independence, ‘it could easily lead to disruption of the new self-governing state, or even to civil war’.[77] To achieve stability and democracy in a new state, Weber argues that ‘universal accessibility of office’ based on merit, is necessary.[78] The Lost Counties lacked this ingredient. Not only were the Banyoro not represented in the kingdom’s censuses, but they were also excluded from political positions. The Secretary of State for African Affairs, a colonial official, disputed this, declaring that there was ‘no obstacle to the appointments of Banyoro to administrative posts… and that a number of such posts are already held by Banyoro’.[79]

However, an analysis of the type of political positions that the Banyoro held, is critical to understanding fragile relationships. The Banyoro were usually appointed as batongole (unpaid village chiefs), which lacked the status of gombolola (sub-county) chiefs.[80] The MBC delegation said: ‘This is the grade [batongole] that the Buganda government has seen fit to give their Bunyoro people … [W]hen we go to the higher ranks it has been noted that at least in Bugangazzi, that no man is gombolola chief.’[81]

The Ugandan historian Karugire described the Banyoro as ‘[political] spectators rather than active participants’, and the significance of this is that there is much to gain from being at the centre of political power as it ‘determines one’s status’.[82] The Banyoro’s low political status and the discrepancies between the groups contributed to a stagnation of political development in Bunyoro.

The marginalisation of the Banyoro within the Lost Counties also negatively affected political development within Bunyoro. Representation is a critical feature of political development and democracy. Having a spokesperson who brings forward grievances is a means to avoid ‘political dismemberment’.[83] Within Buganda and the Lost Counties, the Lukiko (Buganda’s council) was the centre of such ‘representatives’.[84]

The Banyoro, however, were under-represented in council elections. Kasairwe, an informant in 1962, said that the counties made up just four constituencies in Buganda, and that the inhabitants were ‘deprived of their privileges of a democracy to elect their own men who know their problems’.[85] Similarly, in 1959, Governor Crawford announced the creation of a Constitutional Committee which would be ‘based on representation primarily on a population basis’.[86] However, 1959 was the year of the inaccurate census, consequently leading to the Banyoro holding two of the seventy-five seats in the national parliament, compared to Baganda’s holding of twenty, thus reiterating the consequences of inaccurate censuses for democratic representation.[87]

Furthermore, the Banyoro were forbidden from speaking about the Lost Counties issue at the Lukiko. The Resident of Buganda described talks as ‘[neither] necessary, [nor] desirable’, while Gower, the district commissioner described it as ‘arguing the toss’.[88] Consequently, the Baganda’s concerns were prioritised and discussion was prohibited. In response, the MBC referred to Article 15 of the Buganda Agreement, which stated that anybody with grievances could appeal to the king; their pleas, however, were ignored. [89] The threatened declaration of the MBC as an ‘illegal organisation’ for their ‘disturbing [of] peace in Uganda’, was further example of the violation of democratic ideals like freedom of speech.[90] In outrage, the MBC juxtaposed the situation to the ‘good old days’ in Bunyoro when they could politically articulate themselves.[91] This re-emphasises the key claim of this article, that in holding onto their imagined political culture, the Banyoro clashed with the political ‘modernisation’ in Uganda.[92]

The British underestimated the impact the Lost Counties dispute would have on post-independence politics, in part because open discussion of contentious issues was discouraged.[93] As early as 1933 it was written by the Protectorate government that Bunyoro’s native government was ‘reconciled’ to the loss of land and ‘made no attempts’ to re-obtain the counties.[94] From the MBC’s later evidence, we learn that Banyoro in the Lost Counties were not aware of their right to speak out, reiterating the atmosphere of fear in the region:

‘The people in the Lost Counties did not know until very recently that they had the right, the freedom which the British tell us exists in democratic society to argue so freely and openly about this matter. Everybody expects to be arrested.’[95]

The campaign to return the Lost Counties

Established in 1921, the MBC’s ambitions were to return the Lost Counties to Bunyoro and cease the suppression of Bunyoro’s language and customs. The ‘pressure group’ sent petitions to the British in 1933, 1943, 1945, 1948, and 1958 and were often described by their opponents as liars who made ‘false allegations’.[96] Opposed to the assimilation of Banyoro into Buganda’s institutions, the MBC distributed pamphlets, ‘advising their followers not to recognise the Kabaka [Buganda’s king]’, instead urging the group to state their allegiance to the mukama [Bunyoro’s king].[97]

The MBC’s main tactic in the campaign was the politicisation of their precolonial history. Ruth Fisher, a missionary ethnographer from the Church Missionary Society, had written in 1911 that the Banyoro were ‘strangely ignorant of their past’, but further evidence indicates that by the 1920s the glorification of the kingdom’s history was a useful way for the MBC to rally support amongst young people who were reminded that ‘they had an ancestry worthy of pride’.[98] In 1962, lawyers supporting the Banyoro’s case noted that: ‘The history, or rather… the picture of history… is not simply the background to the dispute, it is an essential element in the dispute.’[99]

Nostalgia and nationalism were not merely coping mechanisms for the Banyoro, but a way to advance their political goals. The ‘picture of history’ was crafted by chiefly intellectuals, such as Tito Winyi, Bunyoro’s mukama, with a king list, to demonstrate the prestige of the kingdom, and Nyakatura, who published a book asserting that Bunyoro was ‘extensive, prestigious, and famous… at the height of its power’.[100] The MBC emphasised the pre-colonial greatness of Buyaga and Bugangazzi, the ‘heartland’ of Bunyoro, which held the burial grounds of their mukamas.[101] In doing so, the group hoped to demonstrate the unjustness of the destruction of their kingdom’s status and power.

Such obsession with history served Bunyoro well in terms of strengthening ethnic unity and advancing the policy goal of territorial reunification. But the logic of the historical narratives developed in the Lost Counties campaign promoted the integrity of the kingdom above that of the emerging nation. Moreover, it allowed Bunyoro’s opponents to claim that their heightened historical consciousness was an obstacle to progress and development in politics. Kiwanuka powerfully argued in 1973 that focusing on the past had created an obstacle to development. Banyoro, from this perspective, were wrapped up in nostalgia, preventing the kingdom from looking towards the nation’s future. In this, Kiwanuka was channelling decades of colonial counter-propaganda against Banyoro’s rhetoric, which, while recognising that ‘no nation can succeed without its proper share of national pride’, had urged the Banyoro to make themselves ‘worthy … of the position that you believe rightfully yours’ so that they would receive support and assistance from the Protectorate Government. [102] For the British and the Baganda, all would benefit if the inequities of the past could be forgotten.[103]

Conclusion

It was no coincidence that the name of the newly independent state, ‘Uganda’, seemed remarkably similar to that of ‘Buganda’.[104] The Baganda were victorious in the competition to gain governmental power in the nation state; their close alliance with, and leverage over the British guaranteed this influence. By default, the Banyoro perceived themselves to be the losers. The country was ‘united’ only in theory, with one Muganda, Ndawula Kyambalango, epitomising this sentiment: ‘a person’s enemy is one of his home’.[105]

This article has attempted to produce research which emphasises the political repercussions of Buganda sub-imperialism within the Lost Counties. The article argued that ethnicity is integral to a person’s political identity and often determines who one feels represented by; when language and culture are suppressed in inaccurate censuses and misrepresentative constituencies, local nationalisms are exacerbated. George Magezi, a Munyoro politician, elucidated the dispute very poignantly through a British lens: ‘I know a Scotch will not like to be called an Irish, nor would an Irish be proud to be called a Welsh.’[106] The Banyoro’s politicisation of historical narratives and their emphasis of Bunyoro’s prestige, simply demonstrated the kingdom’s inability to progress.

The Lost Counties dispute plagued Bunyoro for over fifty years and was frequently referred to as an obstacle to stability in the independent nation of Uganda.[107] In 1962, during court testimonies for the return of the Lost Counties, an informant, Mr Majugo, said that if the territorial dispute was not solved before independence, ‘there [would] not be any happiness in the whole country’.[108] And yet as independence neared, the British were ‘anxious to be gone’; Uganda was left, with new borders and a mélange of ethnic groups living together, to resolve the dispute themselves.[109] The dispute was detrimental to political relationships between the Banyoro and Baganda, as the former group had suffered a suppression of their identity, political freedom, and wealth, leaving them with the impression that state politics were dominated by Buganda.[110]

Bibliography (including unquoted sources)

Primary sources

Achebe, Chinua, Things Fall Apart (London: Heinemann, 1967)

Ashe, Robert Pickering, Chronicles of Uganda (London: Cass, 1971)

Baker, Samuel, Ismailia: A Narrative of the Expedition to Central Africa for the Suppression of the Slave Trade (Whitefish: Kessinger, 2000-2009)

Casati, Gaetano, Ten Years in Equatoria and the Return with Emin Pasha (London: Frederick Warne, 1891)

Cunningham, James Frederick, Uganda and Its Peoples: Notes on the Protectorate of Uganda, Especially the Anthropology and Ethnology of its Indigenous Races (London: Hutchinson and Co, 1905)

Felkin, Robert, ‘Notes on the Wanyoro Tribe of Central Africa’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 19 (2014), 136-192

Fisher, Ruth, Twilight Tales of the Black Baganda (Montana: Kessinger, 2006)

Forward, Alan, You Have Been Allocated Uganda: Letters from a District Officer (Dorset, Poyntington Publishing, 1999)

Grant, James Augustus, A Walk Across Africa: Or, Domestic Scenes from my Nile Journey (Whitefish, Kessinger, 2007)

Nyerere, Julius, Freedom and Socialism: A Selection from Writings and Speeches, 1965-1967 (London: Oxford University Press, 1968)

-------, Freedom and Unity: A Selection from Writings and Speeches, 1952-1965 (London: Oxford University Press, 1967)

Postlethwaite, John Rutherfoord Parkin, I Look Back (New York: Boardman, 1947)

Roscoe, John, The Bakitara or Banyoro: The First Part of the Report of the Mackie Ethnological Expedition to Central Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923)

-------, The Northern Bantu: An Account of Some Central African Tribes of the Uganda Protectorate (London: Cass, 1966)

Stanley, Henry Morton, Through the Dark Continent: or, The Sources of the Nile around the Great Lakes of equatorial Africa and down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean (New York: Dover, 1988)

National Archives, Kew Gardens

FCO 141/18324 Uganda: Mubende Banyoro Committee; dispute between Bunyoro and Buganda over the lost counties

FCO 141/18305 Uganda: Bunyoro claims for the return of Bugangaizi, Buyaga and Buwekula (lost counties)

CO 536/171/6 Land Tenure: Bunyoro; committee of enquiry into land tenure and the Kibanja system of tenure

CO 536/178/5 ‘Annual Report on the Social and Economic Progress of the People of the Uganda Protectorate’ for 1932

CO 536/178/10 Bunyoro native administration: Bunyoro Agreement 1933; land policy in Bunyoro and decision in regard to grant of freehold land; points raised by the Mukama of Bunyoro

Evidence Given Before the Commission of Privy Councillors (ECPC); Interview transcripts in possession of Professor Shane Doyle, University of Leeds

Band 1, Evidence from the Delegation of the Mubende Banyoro Committee, 23.01.1962

Band 1, Evidence from Mr Kasairwe, Secretary General, 23.01.1962

Band 2, Evidence from Mr D.A Lury, Government Statistician, 12.01.1962

Band 2, Evidence from Mr Kakunguru, 24.01.1962

Band 2, Evidence from Mr Peter Gibson, Administrative Officer in Uganda, 12.01.1962

Band 3, Mr Foster to Lord Gratiaen, Commission of Inquiry, 12.01.1962,

Band 3, Evidence from Mr Rwamanika, 24.01.1962

Band 7, Evidence from Mr Dunbar to the Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry into “Lost Counties”, 18.01.1962

Band 7, Evidence from Mr Magezi, 15.01.1962

Band 8, Evidence from Mr Majugo, Representing the Banyoro Branch of the UPC, 18.01.1962

(No statement number), Evidence from Mr Zaecheus Haiara Kwebiha, Katikiro of Bunyoro, 13.01.1962

Statement 76, Evidence from Joseph Kalisa, 05.01.1962

Statement Number 77, Evidence from Laboni Musoke, Gombolola of Ssabagabo Bugngazzi

Statement Number 78, Members of the Buwekula Saza Council at the Commission of Inquiry into “Lost Counties”, 15.01.1962

Statement Number 81, Evidence from Mr John Beattie, 17.01.1962

Lawyer’s Rough Notes of Points for Final Speech, 1962

Secondary sources

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson, ‘The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation’, The American Economic Review, 91 (5) (2001), 1369-1401

Adimola, A.B., ‘Uganda: The Newest “Independent”’, African Affairs, 62 (1963), 326-332

Ahiakpor, James, ‘The Success and Failure of Dependency Theory: The Experience of Ghana’, International Organization, 39 (3) (1985), 535-552

Allman, Jean, ‘Between the Present and History: African Nationalism and Decolonization’, in The Oxford Handbook of Modern African History, ed. by John Parker and Richard Reid (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013)

Apter, David, ‘Democracy for Uganda: A Case for Comparison’, Daedalus, 124 (3) (1995), 155-190

-------, The Political Kingdom in Uganda: A Study of Bureaucratic Nationalism (London: Frank Cass, 1997)

-------, ‘The Role of Traditionalism in Political Modernization of Ghana and Uganda’, World Politics, 13 (1) (1960), 45-68

Apthorpe, Raymond, ‘The Introduction of Bureaucracy in African Polities’, Journal of African Administration, 12 (3) (1960), 125-134

Asiimwe, Solomon, ‘Constitutionalism Democratisation and Militarism in Uganda’, Nkumba Business Journal, 15 (2016), 179-194

Austin, Gareth, ‘The ‘Reversal of Fortune’ Thesis and The Compression of History: Perspectives from African and Comparative Economic History’, Journal of International Development, 20 (8) (2008), 996-1027

Bates, Robert, ‘Some Conventional Orthodoxies in the Study of Agrarian Change’, World Politics, 36 (2) (1984), 234-254

Beattie, John, ‘A further note on the Kibanja System of Land in Bunyoro’, The Journal of African Administration, 6 (1954), 178-184

-------, ‘An African Feudality?’, The Journal of African History, 5 (1) (1964), 25-36

-------, ‘Bunyoro through the Looking Glass’, Journal of African Administration, 85 (1960), 85-94

-------, ‘Democratization in Bunyoro: The Impact of Democratic Institutions and Values on a Traditional African Kingdom’, Civilisations, 11 (1) (1961), 8-20

-------, ‘Representations of the Self in Traditional Africa’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 50 (3) (1980), 313-320

-------, ‘The Kibanja System of Land Tenure in Bunyoro’, 6 (1) (1954), 18-28

-------, The Nyoro State (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971)

-------, ‘Rituals of Nyoro Kinship’, Journal of African Administration, 29 (2) (1959), 134-145

Beetham, David, ‘Conditions for Democratic Consolidation’, Review of African Political Economy, 21 (60) (1994), 157-172

Burke, Fred, Local Government and Politics in Uganda (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1964)

Cobbah, Josiah, ‘African Values and the Human Rights Debate: An African Perspective’, Human Rights Quarterly, 9 (3) (1987), 309-331

Doyle, Shane, Crisis and Decline in Bunyoro: Population and Environment in Western Uganda, 1860-1955 (Oxford: James Currey, 2006)

-------, ‘From Kitara to Lost Counties: Genealogy, Land and Legitimacy in the Kingdom of Bunyoro, Western Uganda’, Social Identities, 12 (4) (2006), 457-470

-------, ‘Immigrants and Indigenes: The Lost Counties Dispute and the Evolution of Ethnic Identity in Colonial Buganda’, Journal of East African Studies, 3 (2) (2009), 284-302

-------, Premarital Sexuality in Great Lakes Africa, in Generations Past: Youth in East African History, ed. by Andrew Burton and Helene Charton-Bigot (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2010), 237-261

-------, and Aidan Stonehouse, ‘Uganda’, in Oxford Bibliographies in African Studies, (Oxford University Press, 2013), doi: 10.1093/OBO/9780199846733-0075

Dunbar, A.R., A History of Bunyoro-Kitara (Nairobi: Oxford University Press on behalf of the East African Institute of Social Research, 1965)

-------, ‘The British and Bunyoro-Kitara’, Uganda Journal, 24 (2) (1960), 229-241

Earle, John, Colonial Buganda and the End of Empire: Political Thought and Historical Imagination in Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Espeland, Rune Hjalmar, ‘The Lost Counties: Politics of Land Rights and Belonging in Uganda’, At the Frontier of Land Issues, 2006, 1-13

Fayemi, Ademola Kazeem, ‘Towards an African Theory of Democracy’, Institute of African Studies Research Review, 25 (1) (2009), 101-126

Ferguson, Niall, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World (London: Penguin, 2004)

Frankema, Wout, Erik Green and Ellen Hillbom, ‘Endogenous Processes of Colonial Settlement. The Success and Failure of European Settler Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 34 (2) (2016), 237-265

Geertz, Clifford, Old Societies and New States: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa (London: Collier-Macmillan, 1963)

Geschiere, Peter, ‘Working Groups or Wage Labour? Cash-crops, Reciprocity and Money Among the Maka of Southeastern Cameroon’, Development and Change, 26 (3) (1995), 503-523

Goodfellow, Tom, and Stefan Lindemann, ‘The Clash of Institutions: Traditional Authority, Conflict and Failure of Hybridity in Buganda’, Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 51 (1) (2013), 3-26

Green, Elliott, Ethnicity and Politics of Land Tenure in Central Uganda, Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 44 (3) (2006), 370-388

-------, ‘Understanding the Limits to Ethnic Change: Lessons from Uganda’s ‘Lost Counties’’, Perspectives on Politics, 6 (3) (2008), 473-485

Guyer, Jane, ‘Household and Community in African Studies’, African Studies Review, 24 (2-3) (1981), 87-138

Hall, Susan, The Beginnings of Nyoro Nationalism and the Writers who Articulated it During the Early Colonial Period, 1899-1939 (Doctoral dissertation, Colombia University 1984)

Hanson, Holly Elisabeth, Landed Obligation: The Practice of Power in Buganda (Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2003)

-------, To Speak and be Heard: Seeking Good Government in Uganda, ca. 1500-2015 (Ohio University Press, to be published in August 2022)

Hartmann, Jeannette, ‘The Arusha Declaration Revisited’, The African Review: A Journal of African Politics, Development and International Affairs, 12 (1) (1985), 1-11

Hobsbawm, Eric, The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991 (London: Abacus, 1995)

Hyden, Goran, African Politics in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Ibingira, G.S.K., The Forging of an African Nation: The Political and Constitutional Evolution of Uganda from Colonial Rule to Independence, 1894-1962 (The Viking Press: New York, 1973)

Karugire, Samwiri Rubaraza, A Political History of Uganda (London: Heinemann Educational, 1980)

Kasfir, Nelson, The Shrinking Political Arena: Participation and Ethnicity in African Politics with a Case Study of Uganda (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976)

Keller, Edmond, Identity, Citizenship, and Political Conflict in Africa (Indiana University Press, 2014)

Khan, Mushtaq, ‘Markets, States and Democracy: Patron-Client Networks and the Case for Democracy in Developing Countries’, Democratization, 12 (5) (2005), 704-724

Kiwanuka, M.S.M, ‘Bunyoro and the British: A Reappraisal of the Causes for the Decline and Fall of an African Kingdom’, Journal of African History, 9 (4) (1968), 603-619

-------, ‘Nationality and Nationalism in Africa: The Uganda Case’, Canadian Journal of African Studies, 4 (2) (1970), 229-247

-------, ‘The Diplomacy of the Lost counties and its Impact on Foreign Relations of Buganda, Bunyoro and the Rest of Uganda 1900-1964’, Mawazo, 4 (2 (1974), 111-141

-------, ‘The Empire of Bunyoro-Kitara: Myth or Reality?’, Journal of African Studies, 2 (1) (1968), 27-48

Lonsdale, John, ‘Have Tropical African Nations Continued Imperialism?’, Nations and Nationalism, 21 (4) (2015), 609-629

-------, ‘States and Social Processes in Africa’, African Studies Review, 24 (2-3) (1981), 139-226

Low, Anthony, ‘Defeat: Kabalega’s Resistance, Mwanga’s Revolt and the Sudanese Mutiny’, in Fabrication of Empire: The British and the Uganda Kingdoms, 1890-1902 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 184-214

-------, ‘The British and the Baganda’, International Affairs, 32 (3) (1956), 308-317

Mamdani, Mahmood, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018)

-------, ‘Class Struggles in Uganda’, Review of an African Political Economy, 2 (4) (1975), 26-61

-------, ‘Historicizing Power and Response to Power: Indirect Rule and its Reform’, Social Research, 66 (3) (1999), 859-886

-------, ‘Indirect Rule, Civil Society and Ethnicity: The African Dilemma’, Social Justice, 23 (1-2) (1996), 145-150

-------, Politics and Class Formulation in Uganda (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976)

Médard, Claire, and Valérie Golaz., ‘Creating Dependency: Land and Gift-giving Practices in Uganda’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7 (3) (2013), 549-568

Moradi, Alexander, ‘Commodity Trade and Development: Theory, History, Future’, The History of an African Development: African Economic History Network (2013)

Mujagu, J.B., ‘The Illusions of Democracy in Uganda’, in Democratic Theory and Practice in Africa, ed. by Oyugi Ouma (London: Currey, 1988), 86-99

Mushemeza, Elijah Dickens, ‘Issues of Violence in the Democratisation of Uganda’, Africa Development, 26 (1-2) (2001), 55-72

Nyakatura, John, Anatomy of an African Kingdom: A History of Bunyoro-Kitara (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press, 1973)

O’Connor, Anthony, ‘Uganda: The Spatial Dimension’, in Uganda Now: Between Decay and Development, ed. by Holger Bernt Hansen and Michael Twaddle (London: Currey, 1988), 83-95

Okuku, Juma Anthony, Ethnicity, State Power and the Democratisation Process in Uganda (Sweden: University Printers, 2002)

Oliver, Roland, ‘Traditional Histories of Buganda and Bunyoro’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 85 (1-2) (1955), 111-117

Oluwu, Dele, and James Wunsch, Local Governance in Africa: The Challenges of Democratic Decentralisation (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003)

Oyugi, Ouma, Democratic Theory and Practice in Africa (London: Currey, 1988)

Pengl, Yannick, Philip Roesseler, and Valeria Rueda, ‘Cash Crops, Print Technologies, and the Politicization of Ethnicity in Africa’, The American Political Science Review, 2021, 1-19

Portelli, Alessandro, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in The Oral History Reader, ed. by Robert Perks and Alistair Thompson, (London: Routledge/ Taylor and Francis Group, 2016), 68-78

Peterson, Derek, ‘Violence and Political Advocacy in the Lost Counties, Western Uganda, 1930-1964’, The Internal Journal of African Historical Studies, 48 (1) (2015), 51-72

Pratt, Cranford, ‘Administration and Politics in Uganda, 1919-1945’, in History of East Africa, ed. by V. Harlow and E.Chilver (Oxford: Clarendon press, 1965)

Reid, Richard, A History of Modern Uganda (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017),

------, Political Power in Pre-colonial Buganda: Economy, Society and Warfare in the Nineteenth Century (James Currey, 2002)

Richards, Audrey, East African Chiefs: A Study of Political Development in Some Uganda and Tanganyika Tribes (London: Published for the East African Institute of Social Research by Faber and Faber, 1960)

Roberts, Andrew, ‘The Lost Counties of Bunyoro’, Uganda Journal, 26 (2) (1962), 194-259

------, ‘The Sub-Imperialism of the Baganda’, Journal of African History, 3 (3) (1962), 435-450

Rodney, Walter et al., How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Verso, 2018)

Romaniuk, Scott, ‘Dependency Theory’, in The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives (Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications, 2017), 482-483

Tosh, John, ‘The Cash Crop Revolution in Tropical Africa: An Agricultural Reappraisal’, African Affairs, 79 (314) (1980), 79-94

Uzoigwe, G.N., ‘Bunyoro-Kitara Revisited: A Reevaluation of the Decline and Diminishment of an African Kingdom’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, 48 (1) (2013), 16-34

-------, ‘Pre-colonial Markets in Bunyoro-Kitara’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 14 (4) (1972), 422-455

-------, ‘The Kyanyangire, 1907: Passive Revolt Against British Overrule’, in War and Society in Africa, ed. By B.A Ogot (London: Cass, 1972)

West, Henry, Land and Policy in Buganda (London: Cambridge University Press, 1972)

Wiegratz, Jörg, and E. Cesnulyte, ‘Money Talks: Moral Economies of Earning a Living in Neoliberal East Africa’, New Political Economy, 21 (1) (2016), 1-25

Willis, Justin, ‘Chieftaincy’, in The Oxford Handbook of Modern African History, ed. by John Parker and Richard Reid (Oxford University Press, 2013)

-------, ‘“Peace and Order are in the Interest of Every Citizen”: Elections, Violence and State Legitimacy in Kenya, 1957-1974’, The Internal Journal of African Historical Studies, 48 (1) (2015), 99-116

Wrigley, Christopher, ‘Buganda: An Outline of Economic History’, The Economic History Review, 10 (1) (1957), 69-80

-------, ‘Four Steps Towards Disaster’, in Uganda Now: Between Decay and Development, ed. by Holger Bernt Hansen and Michael Twaddle (London: Currey, 1988), 27-36

Youe, Christopher, ‘Colonial Economic Policy in Uganda after World War One: A Reassessment’, The Internal Journal of African Historical Studies, 12 (2) (1979), 270-276

Zwanenberg, R.M.A, and Anne King, An Economic History of Kenya and Uganda 1800-1970 (London: Macmillan, 1975)

Websites

Buganda.com, ‘The Territory of Buganda’, <www.buganda.com/masaza.htm> [accessed 12 April 2022]

Monitor, ‘Is Museveni Being Honest on Voter Bribery?’, Monitor, <https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/special-reports/elections/is-museveni-being-honest-on-voter-bribery--1631754> [accessed 7 April 2022]

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ‘Identity Politics’, <https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/identity-politics/> [accessed 5 April 2022]

The Economist Group Limited, ‘After 34 years, Uganda’s president has no intention of retiring’, The Economist <https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2021/01/02/after-34-years-ugandas-president-has-no-intention-of-retiring> [accessed 5 April 2022]

The Met, ‘Vessel: 20th Century, Nyoro Peoples’, Met Museum <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/636839> [accessed 4 April 2022]

Endnotes

[2] Evidence Given Before the Commission of Privy Councillors (ECPC), Statement Number 76, Joseph Kalisa, January 1962 (Copy of interviews from the Molson Commission are in the possession of Professor Shane Doyle, University of Leeds).

[3] The Met, ‘Vessel: 20th Century, Nyoro Peoples’, Met Museum <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/636839> [accessed 5 April 2022]

[4] A singular person from Bunyoro is called a ‘Munyoro’, and from Buganda a ‘Muganda’.

[5] Shane Doyle, Crisis and Decline in Bunyoro: Population and Environment in Western Uganda, 1860-1955 (Oxford: James Currey, 2006), p.90.

[6] Henry Morton Stanley, Through the Dark Continent: or, The Sources of the Nile around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean (New York: Dover, 1988), p.403; Robert Pickering Ashe, Chronicles of Uganda (London: Cass, 1971), p.56; Shane Doyle, Crisis and Decline in Bunyoro: Population and Environment in Western Uganda, 1860-1955 (Oxford: James Currey, 2006), p.90.

[7] Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), p.60; Mamdani, Mamdani, ‘Indirect Rule, Civil Society and Ethnicity: The African Dilemma’, Social Justice, 23 (1-2) (1996), 145-150, p.145: ‘Indirect rule’, coined by British colonial officer Lord Lugard, was a system of colonialism employed in Africa, whereby ‘native’ institutions and systems, in theory, were maintained with indigenous people ruling alongside the British.

Cranford Pratt, ‘Administration and Politics in Uganda, 1919-1945’, in History of East Africa, ed. by V. Harlow and E. Chilver (Oxford: Clarendon press, 1965), p.202.

[8] Alan Forward, You Have Been Allocated Uganda: Letters from a District Officer (Dorset: Poyntington Publishing, 1999), p.11; Holly Elisabeth Hanson, Landed Obligation: The Practice of Power in Buganda (Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2003), p.129.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jean Allman, ‘Between the Present and History: African Nationalism and Decolonization’, in The Oxford Handbook of Modern History, ed. by John Parker and Richard Reid (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p.10; Christopher Wrigley, ‘Four Steps Towards Disaster’, in Uganda Now: Between Decay and Development, ed. By Holger Bernt Hansen and Michael Twaddle (London: Currey, 1988), 27-36, p.27.

[11] NA, FCO 141/18305 Uganda: Bunyoro Claims for Return of Bugangaizi, Buyaga and Buwekula (lost counties), Extract from the Intelligence Report for September 1955.

[12] Doyle, ‘From Kitara to Lost Counties: Genealogy, Land and Legitimacy in the Kingdom of Bunyoro, Western Uganda’, Social Identities, 12 (4) (2006), 457-470, p.460.

[13] Roland Oliver, ‘Traditional Histories of Buganda and Bunyoro’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 85 (1-2) (1995), 111-117, p.111.

[14] R.H Espeland, ‘The Lost Counties: Politics of Land Rights and Belonging in Uganda’, At the Frontier of Land Issues, 2006, 1-13, p.8.

[15] Dele Oluwu and James Wunsch, Local Governance in Africa: The Challenges of Democratic Decentralisation (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003), p.5; Points out that we can measure the success of local governance on how much local residents’ concerns are addressed.

[16] Beattie, ‘Bunyoro through the Looking Glass’, Journal of African Administration, 85 (1960), 85-94, p.85.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Fred Burke, Local Government and Politics in Uganda (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1964), p.79; Doyle, ‘From Kitara to Lost Counties: Genealogy, Land and Legitimacy in the Kingdom of Bunyoro, Western Uganda’, p.461.

[19] M.S.M Kiwanuka, ‘The Diplomacy of the Lost Counties and its Impact on Foreign Relations of Buganda, Bunyoro and the rest of Uganda 1900-1964’, Mawazo, 4 (2) (1974), 111-141, p.118.

[20] Hall, The Beginnings of Nyoro Nationalism and the Writers who Articulated it During the Early Colonial Period, 1899-1939, p.225.

[21] Andrew Roberts, ‘The Lost Counties of Bunyoro’, Uganda Journal, 26 (2) (1962), 194-589, p.197.

[22] ECPC, Band 7, Evidence from Mr Magezi, 15.01.1962. “The people in the Lost Counties did not know until very recently that they had the right, the freedom which the British tell us exists in democratic society to argue so freely and openly about this matter.”

[23] Juma Anthony Okuku, Ethnicity, State Power and the Democratisation Process in Uganda (Sweden: University Printers, 2002), p.2.

[24] Beattie, ‘Democratization in Bunyoro: The Impact of Democratic Institutions and Values on a Traditional African Kingdom’, Civilisations, 11 (1) (1961), 8-20, p.13.

[25] Willis, ‘Chieftaincy’, p.6.

[26] NA, CO 536/171/8, Bernard Henry Bourdillon, signed in the presence of Provincial Commissioner, Northern Province.

[27] NA, CO 536/171/6, J.G Rubie and H.B Thomas, Report of the Commission of Enquiry into Land Tenure and the Kibanja System in Bunyoro; Goran Hyden, African Politics in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p.72.

[28] Beattie, The Nyoro State (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), p.169.

[29] Ruth Fisher, Twilight Tales of the Black Baganda (Montana: Kessinger, 2006), p.33.

[30] Peter Geschiere, ‘Working Groups or Wage Labour? Cash Crops, Reciprocity and Money Among the Maka of South Eastern Cameroon’, Development and Change, 26 (3) (1995), p.504.

[31] John Earle, Colonial Buganda and the End of Empire: Political Thought and Historical Imagination in Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p.25; Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991 (London: Abacus, 1995), p.201 (Italics added by me).

[32] ‘Official’ sources include exchanges between Governors, Secretaries of State, Residents of Buganda, and the District Commissioner’s Office, and reports such as J.G Rubie and H.B Thomas’ Report of the Commission of Enquiry into Land Tenure and the Kibanja System in Bunyoro.

[33] Alessandro Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, in The Oral History Reader, ed. By Robert Perks and Alistair Thompson (London: Routledge/ Taylor and Francis Group, 2016) p.53.

[34] ECPC, Statement Number 81, Evidence from Mr John Beattie, 17.01.1962.

[35] Ibid.

[36] The number and origin of Bunyoro’s Lost Counties is a point of contention in Ugandan history. Certain accounts, including this one, argue that five and a half of Bunyoro’s counties were given to Buganda, while others suggest that seven were given (with additions of Buddu, Singo, and Bulemezi). Such disputes are revealing about the Lost Counties issue as they demonstrate a fundamental imprecision at the heart of the Lost Counties case. Kiwanuka, ‘Bunyoro and the British: A Reappraisal of the Causes for the Decline and Fall of an African Kingdom’, Journal of African History, 9 (4) (1968), 603-619, p.614.

[37] NA, FCO 141/18324, Letter from Erisa Kalisa, Joseph Nagaisure, James Mkasa and others, to Honourable Resident, Keith Hancock.

[38] Buganda.com, ‘The Territory of Buganda’, <www.buganda.com/masaza.htm> [accessed 12 April 2022].

[39] NA, CO 536/178/10, Deputy to the Governor to the Right Honourable the Secretary of State for the Colonies, 26.08.1933.

[40] Mamdani, ‘Historicizing Power and Response to Power: Indirect Rule and its Reform’, Social Research, 66 (3) (1999), 859-886, p.860.

[41] Ibid., p.866.

[42] Clifford Geertz, Old Societies and New States: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa (London: Collier-Macmillan, 1963), p.108.

[43] Hall, The Beginnings of Nyoro Nationalism and the Writers who Articulated it During the Early Colonial Period, 1899-1939, p.12.

[44] Anthony Low, ‘The British and the Baganda’, International Affairs, 32 (3) (1956), 308-317, p.310; Christopher Wrigley, ‘Four Steps Towards Disaster’, p.29; A.R Dunbar, A History of Bunyoro-Kitara (Nairobi: Oxford University Press on behalf of the East African Institute of Social Research, 1965), p.110.

[45] Hanson, To Speak and be Heard: Seeking Good Government in Uganda, ca. 1500-2015, p.113; Nelson Kasfir, The Shrinking Political Arena: Participation and Ethnicity in African Politics with a Case Study of Uganda (Berkley: University of California Press, 1976), p.5.

[46] Kiwanuka, ‘Nationality and Nationalism in Africa: The Uganda Case’, Canadian Journal of African Studies, 4 (2) (1970), 229-247, p.231.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Hall, The Beginnings of Nyoro Nationalism and the writers who Articulated it During the Early Colonial Period, 1899-1939, p.255.

[49] Geertz, Old Societies and New States: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa, p.110.

[50] Edmond Keller, Identity, Citizenship and Political Conflict in Africa (Indiana University Press, 2014), p.11.

[51] Okuku, Ethnicity, State Power and the Democratisation Process in Uganda, p.11.

[52] Green, ‘Understanding the Limits to Ethnic Change: Lessons from Uganda’s ‘Lost Counties’’, p.477

[53] Ibid, p.474.

[54] The Saza Council was comprised of Baganda chiefs so arguably not fully representative of the Banyoro in the Lost Counties; ECPC, Statement Number 78, Members of the Buwekula Saza Council at the Commission of Inquiry into “Lost Counties”, 15.01.1962.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Runyoro is the language of the Banyoro, and Luganda is the language of the Baganda. James Augustus Grant, A Walk Across Africa: Or, Domestic Scenes from my Nile Journey (Whitefish: Kessinger, 2007), p.291; Robert Felkin, ‘Notes on the Wanyoro Tribe of Central Africa’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 19 (2014), 136-192, p.166.

[57] ECPC, Statement Number 77, Evidence from Laboni Musoke, Gombolola of Ssabagabo Bugangazzi.

[58] NA, FCO 141 183 05, Governor’s Deputy, Uganda Reference LC.C.161.1, Bunyoro’s Claim for the Return of Bugangadyi and Buyaga.

[59] ECPC, Band 7, Evidence from Mr Dunbar to the Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry into “Lost Counties”, 18.01.1962.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Kiwanuka, ‘The Empire of Bunyoro-Kitara: Myth or Reality?’, Journal of African Studies, 2 (1) (1968), 27-48, p.27.

[62] Portelli, ‘What Makes Oral History Different’, pp.52-53.

[63] Lawyer’s Rough Notes of Points for Final Speech at Commission of Inquiry into “Lost Counties”, 1962. (Italics have been inserted by me).

[64] Buyaga and Bugangazzi voted in a 1964 referendum to return to Bunyoro.

[65] NA, FCO 141/18324, Claim for the Restoration to the Bunyoro Kingdom of the 5.5 Counties at one time Ceded to the Buganda Kingdom, to R.H Her Majesty’s Secretary of State, 26.10.1953.

[66] ECPC, Band 2, Evidence from Mr Peter Gibson, Administrative Officer in Uganda, 12.01.1962.

[67] ECPC, Band 2, Evidence from Mr D.A Lury, Government Statistician, 12.01.1962.

[68] ECPC, Band 3, Evidence from Mr Rwamanika, 24.01.1962.

[69] NA, FCO 141/18324, Claim for the Restoration to the Bunyoro Kingdom of the 5.5 Counties at one time Ceded to the Buganda Kingdom, to R.H Her Majesty’s Secretary of State, 26.10.1953; The Banyoro did not have access to the same quality of education as the Baganda because the North was used as a base for military and migrant labour. Baganda were also more likely to be granted scholarships for university.

[70] ECPC, Band 2, Evidence from Mr Peter Gibson, Administrative Officer in Uganda, 12.01.1962.

[71] A.B Adimola, ‘Uganda: The Newest “Independent”’, African Affairs, 62 (1963), 326-332, p.329. There were 83 constituencies established in 1960.

[72] Romaniuk, ‘Dependency Theory’, p.2; Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Verso, 2018), p.11.

[73] As an example, Buganda received better schools and hospitals, while Bunyoro become home to the military and migrant labour. Apter, ‘Democracy for Uganda: A Case for Comparison’, Daedalus, 124 (3) (1955), 155-190, p.156; Zwanenberg, An Economic History of Kenya and Uganda, 1800-1970, p.67.

[74] NA, FCO 141/18324, Signed by Erisa Kalisa, Joseph Kasairwe and others, to the Right Honourable Secretary of State for the Colonies.

[75] NA, FCO 141/18324, MBC to the Right Honourable, Her Majesty’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, London, 26.10.1953.

[76] Mushemeza, ‘Issues of Violence in the Democratisation of Uganda’, p.57.

[77] Apter, ‘Democracy for Uganda: A Case for Comparison’, p.160; Green, ‘Understanding the Limits to Ethnic Change: Lessons from Uganda’s ‘Lost Counties’’, p.481.

[78] Max Weber, ‘Bureaucracy’, in Weber’s Rationalism and Modern Society: New Translations on Politics, Bureaucracy, and Social Stratification, cited in Oyugi, Democratic Theory and Practice in Africa, p.107.

[79] NA, FCO 141/18324, Secretary of State for African Affairs to the Banyoro Committee, to Erisa Kalisa, President of MBC, 19.08.1954.

[80] Richards, East African Chiefs: A Study of Political Development in Some Ugnadna and Tanganyika Tribes, p.58: Batongole were ‘men put in charge of work’.

[81] ECPC, Band 1, Evidence from the Delegation of the Mubende Banyoro Committee, 23.01.1962.

[82] Karugire, A Political History of Uganda, p.144; Kiwanuka, ‘The Diplomacy of the Lost Counties and its Impact on Foreign Relations of Buganda, Bunyoro and the rest of Uganda 1900-1964’, p.118.

[83] Geertz, Old Societies and New States: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa, p.114; Afrifa Gitonga, ‘The Meaning and Foundations of Democracy’, in Democratic Theory and Practice in Africa, p.13.

[84] Kiwanuka contends that the Baganda at the Lukiko ‘had a noble aim of expressing the fears of all the Africans in Uganda’. Hanson also argues that anybody was free to speak at the Lukiko; Hanson, To Speak and be Heard: Seeking Good Government in Uganda, ca. 1500-2015, p.108; Kiwanuka, ‘Nationality and Nationalism in Africa: The Uganda Case’, p.235.

[85] ECPC, Band 1, Evidence from Mr Kasairwe, Secretary General, 23.01.1962.

[86] G.S.K Ibingira, The Forging of an African Nation: The Political and Constitutional Evolution of Uganda from Colonial Rule to Independence, 1894-1962 (The Viking Press: New York, 1973), p.94.

[87] Ibid., p.94.

[88] NA, FCO 141/18324, Resident of Buganda, 01.08.1956; K.P Gower to District Commissioner’s Office.

[89] NA, FCO 141/18324, MBC to Andrew Cohen, Governor of Uganda, May 1952; Katikiro of Bunyoro to Katikiro of Buganda, 23.04.1956.

[90] NA, FCO 141/18324, Katikiro, Omulamuzi, Omuwanika and others to the Resident of Buganda, 03.11.1955; ECPC, Band 2, Evidence from Mr Kakunguru, 24.01.1962.

[91] NA, FCO 141/18324, MBC to Andrew Cohen, May 1952.

[92] Ibid.

[93] NA, FCO 141/18305, Extract from the Intelligence Report for September 1955; it was written: ‘there is no reason to support that they [the Banyoro] will ever do anything more than petition about it’.

[94] NA, CO 536/178/10, Bunyoro Agreement, 1933.

[95] ECPC, Band 7, Evidence from Mr Magezi, 15.01.1962.

[96] Kiwanuka, ‘The Diplomacy of the Lost Counties and its Impact on Foreign Relations of Buganda, Bunyoro and the rest of Uganda 1900-1964’, p.116; FCO 141 183 24, Evidence from Ndawula Kyambalango.

[97] NA, FCO 141/18324, Ndawula Kyambalango; When the Mukama passed through the Counties, the MBC said that Banyoro were “very eager to see him because they felt, naturally, that he was their ruler and they wished to be reunited with him”; Band 1, Evidence given by the Delegation of the MBC, Mr Rugemwa, 23.01.1962.

[98] Fisher, Twilight Tales of the Black Baganda, p.vi; G.N Uzoigwe, ‘Bunyoro-Kitara Revisited: A Reevaluation of the Decline and Diminishment of an African Kingdom’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, 48 (1) (2013), 16-34, p.18.

[99] ECPC, Lawyer’s Rough Notes of Points for Final Speech, 1962.

[100] Hall, The Beginnings of Nyoro Nationalism and the Writers who Articulated it During the Early Colonial Period, 1899-1939, p.181.

[101] Derek Peterson, ‘Violence and Political Advocacy in the Lost Counties, Western Uganda, 1930-1964’, The Internal Journal of African Historical Studies, 48 (1) (2015), 51-72, p.52.

[102] NA, CO 536/178/10, Text of Her Excellency the Governor’s Speech on the Occasion of Signing the Bunyoro Agreement at Hoima, 23.10.1933.

[103] Richard Reid, A History of Modern Uganda (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), Introduction.

[104] Phonetically, Buganda is pronounced by its citizens with a silent ‘b’, ‘Uganda’.

[105] NA, FCO 141 183 24, Evidence from Ndawula Kyambalango.

[106] Band 7, Evidence from Mr Magezi, 15.01.1962.

[107] NA, CO 536/178/10, The Text of His Excellency the Governor’s Address to the Legislative Council at the Meeting on 21.11.1933; He declared ‘If it [Uganda] does not go forward then it will definitely stagnate and go backward’.

[108] ECPC, Band 8, Evidence from Mr Majugo, Representing the Banyoro Branch of the UPC, 18.01.1962.

[109] Wrigley, ‘Four Steps Towards Disaster’, p.33.

[110] Doyle, Immigrants and Indigenes: The Lost Counties Dispute and the Evolution of Ethnic Identity in Colonial Buganda’, Journal of East African Studies, 3 (2) (2009), 284-302, p.288; Young also notes that “although we described the independent polities as ‘new states’, in reality they were successors to the colonial regime, inherited its structures”, cited in Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson, ‘The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation’, The American Economic Review, 91 (5) (2001), 1369-1401, p.1376.