Skin Colour in Ancient Greece: The Insertion of a Non-Existent Colour Prejudice into Antiquity.

By Maya Aziz

This article is an abridged version of an undergraduate dissertation, titled “Skin Colour in Ancient Greece: The Insertion of a Non-Existent Colour Prejudice into Antiquity" with which Maya Aziz (School of Languages, Cultures and Societies) completed her BA in Classics at the University of Leeds. Together with Kerry Pearson, she was awarded the 2022 Lionel Cliffe Prize for the best undergraduate dissertation on a topic relevant to African Studies at the University of Leeds.

Introduction

Skin colour is central to issues of race in twenty first-century society. This, however, has not always been the case. Ancient Greece lacked a divide between ‘Black’ and ‘White’ races, yet the Greeks have been consistently invoked to demonstrate White, European superiority. This study explores the absence of colour prejudice in Greece and explains that, ultimately, classifications of ‘Black’ and ‘White’ are modern inventions. This does not mean that the Greeks lacked prejudices towards others – they did. The point, however, is that these prejudices were not based on ‘Black’ and ‘White’.

This study looks at ancient Greek representations of Black people in their art and literature. What I mean by ‘Black’ should be clarified, since the concept itself is absent from Greek thought[1]. I discuss people who are described as having ‘black’ skin. The study therefore largely focuses on representations of Ethiopia, with reference to Egypt and India where appropriate. The consensus is that Ethiopians epitomised Blackness for the Greeks. Snowden (1970, p.2) describes Ethiopians as the ‘yardstick’ for measuring colour, and Gruen (2011, p.202) argues that they became ‘virtually synonymous’ with Blackness. This idea is corroborated in the ancient sources, from Aristotle’s claim that Ethiopian skin is ‘darker than that of any other people’ (Arist. Prob. 10.666), to Arrian’s observation that Indians are darker than all other men, ‘except the Ethiopians’ (Arr. An. 5.4.4). Given that Ethiopia provides the clearest representation of Blackness in ancient Greece, it is the focus of this investigation of colour prejudice.

The vagueness of the term ‘ancient Greeks’ should be addressed. This study references sources ranging from the eighth century B.C.E. to the third century C.E., so the opinions and attitudes we encounter are not constant nor wholly representative of so many peoples over such a large time-span. This study does not aim to gain insights into specific views of specific groups of people. Rather, it aims to gather the available evidence in order to show that many of the issues surrounding skin colour familiar to us are modern creations, and attempts to trace their development back to ancient Greece are inaccurate. The overall take-away from this study should not be that ‘all Greeks thought about skin colour in this way’; rather that, in general, modern prejudices formed around skin colour are absent from ancient Greek thought.

The study begins by looking at ancient Greek views of black skin. First, we consider the Greeks’ oppositional mode of self-definition, which created the foundational concepts of ‘Greek’ and ‘Barbarian’. Next, we look at environmental theory, another central concept, which explained differences in skin colour and character through proximity to the sun. Following this, we consider the polarity between dark and light in mythology, to illustrate the difference in their usage in ancient Greece. In art, we look at Janiform vases and consider their reception as caricature, before recognising neutral depictions of the Black barbarian in Greek art. Moving back towards literature, we consider themes of savagery, before concluding that such negative judgements were not made with reference to skin-colour, but cultural practice.

After consideration of ancient Greek views, we move to the Enlightenment, and see how views of skin colour differed, and how theorists misappropriated Greece. First, we look to notions of ‘Whiteness’ as beautiful and denoting normalcy, as a matter of science. Following this, we consider the longevity of ‘savage’ imagery surrounding Ethiopia and see how Enlightenment accounts of ‘savagery’ contain colour prejudices absent from ancient accounts. Finally, we move to the twenty-first century and see that the use of antiquity to justify white supremacy is still an issue, by examining the invocation of Greece on White Supremacist websites.

Self-Definition Through Polarities: Constructing Greek Identity

The Greeks lacked a clear sense of identity (as Greeks)[2] until the Persian Wars (499 B.C.E.- 448. C.E.). The first question to ask, then, is: what changed? What about this event united once disparate groups? As Sassi (2001, p.101) puts it, the Greeks gained a collective identity, superimposed over city-state and regional identities, through the military partnership between Athens and Sparta (two of the strongest city-states in many eras of Greek antiquity). Through collaboration amongst individual city-states coupled with increased contact with common enemies, the Greeks simultaneously began viewing themselves as united and other cultures as different. These two observations came together to develop the idea of ‘the barbarian’ as opposite to ‘the Greek’[3].

The Greeks adopted what Hall (1997, p.47) calls an ‘oppositional’ mode of self-definition, in which the ‘barbarian’ served to encompass everything non-Greek and, by extension, served to define everything Greek. Thucydides notes that, prior to the Trojan War, the name ‘Hellas’ (the Greek word for ‘Greece’) was not ‘universal’. He cites Homer’s omission of the term ‘barbarian’, attributing this is to ‘the Grecians’ being ‘not yet distinguished by one common name of Hellenes’ (Thuc. 1.3.1-4). Here, we have confirmation of oppositional self-definition, alongside the recognition that the Greeks had not always been united and that, therefore, there was no standard opposition between ‘Greek’ and ‘barbarian’. This supports the idea that the barbarian serves primarily to define the Greek. It is crucial to understand this process of self-definition and the use of polarities to define because, as we will see, it underlies so much of the Greek attitude towards foreign peoples.

Environmental Theory

Use of the label ‘Aithiops’ (‘burnt-face’) to refer to a person with black skin will strike twenty-first century readers as offensive. This, as Gruen (2011, p.197) notes, was a Greek term to describe Ethiopians, and the etymological root of their name. Initial discomfort with the term stresses the importance of understanding Greek modes of thought surrounding the ethnic ‘other’, in order to explain why they referred to Black people thus. Once we read such representations contextually, we see that this description is not intended to offend, but reflects the Greek method of explaining physical variation through climate.

The Greeks explained black skin through proximity to the sun. This in itself seems a reasonable, albeit inaccurate, judgement to make. The theory that climate affected physical appearance was laid out in Airs, Waters, Places[4] and adopted by many ancient writers, from Herodotus’ assertion that Ethiopians are ‘black because of the heat’ (Hdt. 2.22), to Aeschylus describing the Egyptians as a ‘sun-burned race’ (Aesch. Supp. 154-155). It is significant that the theory was not employed solely to explain black skin. Those who lived closer to the sun had dark skin, those who lived further from it were paler. We see this in the idea that, in terms of physique, Egyptians are impacted by the heat, and Scythians by the cold (Hp. Aer. 18), which ‘burns’ their ‘white skin’ (Hp. Aer. 20). The theory applies to people of all skin tones. Climate also affected character. Airs states that Europe and Asia ‘differ in every respect’, describing Asians as ‘gentle’ due to climate (Hp. Aer. 12). Herodotus reflects this in his account of Cyrus’ response to the proposal that the Persians leave ‘rugged’ Persia and occupy a better land. Cyrus claims that, if they were to do so, they would no longer be rulers, claiming that ‘wondrous fruits of the earth and valiant warrior never grow from the same soil’ (Hdt. 9.122).

The idea that climate affects character is dangerous because, as Isaac (2006, pp. 163-165) points out, it created common characteristics which became subject to a hierarchy – an idea adopted eagerly by racist theorists. I am certainly not positing racism into Greek environmental thought. Greek ideas have been modified and misinterpreted by subsequent proponents, but that only reinforces the importance of studying ancient ideas separately from modern conceptions of race. Greek environmental thought did not discriminate on the basis of skin colour. Character-judgements were made but, as Snowden (1970, p.176) notes, the theory explained racial diversity uniformly regarding people of all skin tones. We can view environmental theory as part of the Greek desire to understand the ‘other’ and, by extension, themselves. The theory was, admittedly, self-serving, granting the Greeks superior characteristics, and it did enforce a hierarchy. However, judgements were not made because of skin colour, were not limited to Black people, and did not serve anything like the systemic racism present in modern society. The theory recognised both positive and negative qualities of peoples, with reference to their climate.

Dark and Light in Mythology

I have noted that uses of the colour terms ‘black’ and ‘white’ today differ from their uses in Greece, reflecting their connotations in mythology. Snowden (1991, p.84) recognises the Greek tendency to associate white with goodness and Olympus (the home of the gods in Greek religion), and black with badness and the underworld. Aeschylus describes ‘the black abyss of Hades’ (Aesch. PB. 432-433), Euripides talks of ‘black death’ (Eur. Tro. 1302), and Hesiod attributes chaos to the ‘black Night’ (Hes. Th. 123-125). Naturally, many examples of blackness in myth hold negative connotations.

The important question to ask is whether the negative associations attached to blackness in mythology transferred to people with black skin. Snowden (1991, p.84) argues against this, doubting that expressions like ‘blacklist’ or ‘black-hearted’ would create prejudice against those with black skin in the modern world in the absence of phenomena like the African slave trade and colonialism. Since the Greeks did, in fact, operate in a society lacking such phenomena, the negativity attached to blackness in mythology seems unlikely to have transferred to those with black skin. Here, we return to the importance of reading antiquity within its own context. As we have seen from their environmental theory, the Greeks did not view themselves as ‘White’, so the idea that whiteness and goodness applied to Greeks and blackness and badness to the black barbarian does not follow from the mythological status of the colour terms. To read Greek myth thus would be to read it through a modern, therefore anachronistic, lens.

Cruel Intentions? Opposition in Art

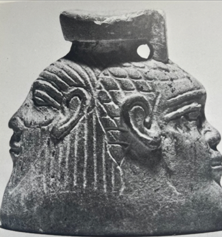

Fig 1: Perfume vase juxtaposing a head of a White man and a Black man. From Cyprus. Late fourth century or early fifth century B.C.E. (Snowden, 1976, Fig. 149).

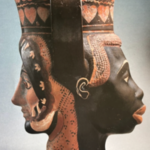

Fig. 2. Kantharos in the form of the conjoined heads of a White woman and a Black man. Late sixth century B.C.E. Terracotta. (Snowden, 1976, Fig.160)

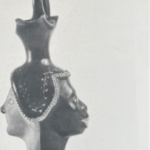

Fig.3. Kantharos in the form of the conjoined heads of Heracles and a Black man. From Delphi. Fifth century B.C.E. Terracotta. (Snowden, 1976, Fig. 193).

Fig. 4. Oinochoe in the form of the conjoined heads of a White woman and a Black man. From Vulci. Fifth Century B.C.E. Terracotta. (Snowden, 1976, Fig. 159).

We should turn our attention towards Greek art, specifically Janiform vases depicting Black and White heads side-by-side (Figs. 1-4). Their reception varies: some perceive them as caricature, intending to mock the Black people they portray. I argue that this is misguided – the vases do not serve to mock the Black people they depict – and that such assumptions reflect modern prejudices surrounding skin colour.

The vases’ manufacture is telling: Gruen (2011, p.216) notes that the heads are crafted from the same mould, and Bérard (2000, p.410) emphasises the balanced treatment of subjects, noting that each head is crafted with the same degree of attention. Both deny that anything in this craftsmanship suggests intent to portray either as superior to the other. We must ask, then, if the vases are crafted so as to suggest no imbalance, why have many interpreters disagreed? At first sight, the contrast is rather striking, and encourages comparison. This would not, however, to ancient viewers, necessarily encourage an imbalanced reception. The potential discomfort greeting modern viewers reflects modern connotations attached to blackness and whiteness which were absent among the Greeks. Of course, the Greeks often viewed themselves as superior to other peoples; however, these judgements were not made on the basis of physical appearance. In fact, Bérard (2000, p.411) argues that the opposition of the two heads serves to celebrate the appearance of both heads – the artist does not hold one side as beautiful and the other as ugly, but works to represent classical beauty on one side and ‘exotic’ beauty on the other. Greek viewers may well have regarded themselves as better than Ethiopians; however, the vases themselves do not support this narrative. Where modern commentators may see an imbalance, ancient viewers likely saw only a showcase of differences between two people, with no suggestion of inferiority in one half of the vase.

Not Always ‘Other’: Neutral Depictions in Art

Fig. 5. Bronze jockey with hair resembling that of several other depictions of Black people. From Cape Artesium. Hellenistic period. Likely a black-white cross (Snowden, 1970, Fig. 63)

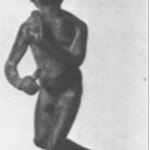

Fig. 6. Bronze statuette of a dancer. Hellenistic. From Erment. Egypt. (Snowden, 1970, Fig. 103).

Fig. 7. Bronze dancer. From Herculaneum. Hellenistic. (Snowden, 1970, Fig. 103).

Fig. 8. Statuettes of boxers, tightly curled hair, broad nose, thick lips. Late Hellenistic. (Snowden, 1970, Fig. 49).

Fig. 9. Terracotta of an athlete. Hellenistic. (Snowden, 1970, Fig. 106)

It is significant that, although notice was paid to the alterity of Black people, they often enjoyed neutral depictions presenting them in the same manner as Greeks. Gruen (2011, pp. 210-211) cites depictions of Black jockeys (Fig. 5), dancers (Figs. 6-7), and athletes (Figs. 8-9). This range of depictions shows that not all representations of Black people served to showcase their difference, demonstrating that the Greeks were familiar with Black people and, although they were aware of their alterity, it did not prevent them from enjoying representations transcending the archetype of ‘other’ or ‘barbarian’.

Savagery vs Civilisation: The Duality of Ethiopia in Literature

We encounter descriptions of ‘uncivilised’ Ethiopians in literature, in which Black people are represented as savage. Diodorus describes some Ethiopians as ‘entirely savage’, with natures comparable to ‘wild beast[s]’ (Diod. 3.8.2), Agatharchides cites nudity and sharing of wives (Agatharchides, De Mari Erythraeo 5.62b), and Herodotus speaks of ‘cave-dwelling’ Ethiopians who ‘live on snakes and lizards’ (Hdt. 4.183). Allahar (1993, pp.3-5) appeals to such descriptions in claiming that the Greeks viewed Ethiopians as ‘different, inferior, savage, and lacking in morals’. Allahar’s claim represents the wider narrative that themes of savagery within some Greek accounts of Ethiopia showcase an overarching negativity towards Black people. In response to this, two points will be made. Firstly, that savage descriptions represent only a minority of references to Ethiopia in literature; secondly, that ‘savagery’ was not limited to Black people.

To address my first point, we must contextualise savage descriptions which, as Smith (2001, p.30) observes, represent only one half of a binary – the other being civilised Ethiopians. Didorus’ civilised Ethiopians follow the Homeric tradition: Homer’s Ethiopians are praised as ‘blameless’ people, with whom the gods enjoyed feasting (Hom. Il. 1.420-425). Diodorus acknowledges this in his description of Homer as ‘the oldest and certainly the most venerated’ author amongst the Greeks (Diod. 3.2.2). This recognition of Homer’s influence, and therefore the value of his image of Ethiopia, shows that those savage descriptions are not intended to represent Ethiopia as a whole. Diodorus also asserts that Ethiopia conquered Egypt, the ‘larger part’ of Egyptian customs being Ethiopian (Diod. 3.3.3), including the ‘shapes of their statues’ and ‘forms of their letters’ (Diod. 3.3.4-5). Snowden (1970, p.120) denies bias in such commentaries, evidenced by the readiness of writers to assert Ethiopian achievements. It is easy to see how, when considered alone, savage imagery could create the impression of prejudice towards Ethiopia. However, when we consider the evidence at large, we see that such imagery constitutes only a portion of the broader Greek view of Ethiopia. In fact, the sources themselves suggest that these descriptions are not entirely accurate. Diodorus recognises that some of his sources have accepted ‘false report’ while others have ‘invented many tales out of their own minds’ (Diod. 3.11). Ephorus warned that reports of far-away people were popular because ‘the terrible and marvellous are startling’, but that we must account for the opposite facts (Strab. 7.3.9). We get the impression that some descriptions serve to entertain with tales of far-away lands, rather than present accurate depictions of Ethiopia.

Now for my second point – other far away peoples being described using similar language. There were ‘wild’ Ethiopians, but also ‘savage’ Scythians (Hdt. 4.106). In a description reminiscent of those of savage Ethiopians, Herodotus describes Scythians as ‘the most savage of all men’ who ‘know no justice and obey no law’ (Hdt. 4.106). This brings us back to the idea discussed concerning environmental theory, that judgements were made about Ethiopians surrounding their proximity to the sun, but also about Scythians regarding their distance from it. Likewise, Greek writers described Ethiopians as savage, but described Scythians similarly. McCoskey (2019, p.45) points out the correlation between the geographic distance and the ‘likeness’ or ‘strangeness’ of cultures. ‘Savage’ Ethiopians and Scythians served to represent those far away cultures, not to promote non-existent anti-Black views. Admittedly, the descriptions are not without judgement; however, these judgements were not made on the basis of skin-colour.

Culture is Key!

My argument thus far is that the Greeks did discriminate against people who differed from them, ranking themselves first in a self-made hierarchy, but not on the basis of skin-colour, and not like racism in modern society. The question remains: if skin-colour did not drive discrimination, what did? I argue, by examining Herodotus, that culture was the key reason the Greeks viewed another nation as relevantly different from and inferior to them.

Herodotus’ recognition of cultural relativity is interesting. He does make judgements, both positive and negative, on the customs of barbarians, but is aware that, as Thomas (2000, p.131) puts it, ‘barbarians have their own barbarians’. This is reflected in his claim: ‘if it were proposed to all nations to choose which seemed the best of all customs, each, after examination, would place its own first; so well is each convinced that its own are by far the best’ (Hdt. 3.38.1). It is clear that the Greeks place themselves first in their own hierarchy, but that other nations do the same, placing the Greeks lower down on theirs. Herodotus, then, contextualises his own claims: he does make judgements, but recognises that they are guided by man’s conception that his own culture is superior. To exemplify this, Herodotus portrays Darius asking the Greeks and Indians about their respective treatments of the dead[5]. First, Darius asked the Greeks ‘for what price they would eat their fathers’ dead bodies’, to which they replied ‘there is no price for which they would’. He then asked the Indians ‘what would make them willing to burn their fathers at death’, to which the Indians ‘cried aloud that he should not speak of so horrid an act’. Both peoples, who are barbarians to one another, are appalled by the other’s customs; and so, Herodotus concludes, ‘custom is lord of all’ (Hdt. 3.38-4). The Greeks and Indians differ in physical appearance, but this exchange gives the impression that, above all, culture makes these men fundamentally different.

Culture was the main determining factor in how different peoples were from the Greeks. Observations surrounding skin-colour contributed to this differentiation but were much more a product of curiosity than grounds to make substantial judgements. Discrimination was present amongst the Greeks, and we have seen that they often placed themselves above others, but Herodotus’ notion of cultural relativity, alongside diverse depictions in art and literature, allows us to see that the Greek/barbarian polarity as not always as rigid as ‘superior Greeks’ and ‘inferior barbarians’. We see a recognition that all cultures differ, and Herodotus does portray the Greeks in a favourable light, as do other authors, but, crucially, he recognises that his narrative is not the only one.

Modern Notions of Skin Colour

Throughout this essay, I have referred to the danger of viewing antiquity through a modern lens: that lens will now be explored. I look to the rising influence of notions of Blackness and Whiteness in racial thought, and how scholars during the Enlightenment constructed a racial discourse centred around aesthetics and skin colour. By looking back to the period when skin colour gained centrality in theories of race, while considering the invocation of ancient Greece to push White supremacy, we will understand the inaccuracy of importing colour prejudice into ancient Greece, by recognising the starkly different contexts of ancient and modern theories.

The Science of Western Beauty

Fig. 10. A Classical Greek profile juxtaposed with those of a Black man and an ape. 1794. (Jahoda, 1999, Fig. 6.1).

Fig. 11. Camper’s illustration of facial angles. 1794. (Jahoda, 1999, Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 12. Bell’s invocation of Camper’s facial angle, 1847. (Bell, 1847, p.25).

Fig. 13. Bell’s contrast of the head of a Black man and the head of M.Agrippa, using Camper’s facial angle. 1847. (Bell, 1847, p.30)

Skin colour was important to Enlightenment theorists and ‘White’ had come to denote normalcy. Tied into ideas of Whiteness and Blackness was the notion of beauty. Mitter (2011, p.68) admits that Enlightenment Europeans were not alone in believing themselves to be supremely beautiful, but they were the only society that elevated the concept to the level of scientific objectivity. We now explore the invocation of Greece to justify White beauty and Black ugliness as grounded in science.

Let us return to environmental theory, as exemplifying the centring of whiteness in enlightenment theories of race. We saw that, in Greece, the theory explained differences between Greeks and other peoples, and justified Greek superiority. George-Louis Buffon (1766, pp.311-374), as detailed by Isaac (2004, p.9), argued that ‘normal’ man, being the White man, had grown blacker in hotter climes, and could return to his original colour by moving to a cooler environment. The general idea resonates with that of the Greeks, aside from the ‘normal’ man being White. We have seen that, in their environmental theory, white skin was reserved for Scythians, who were as ‘barbaric’ to the Greeks as the Black Ethiopians. For the Greeks, whiteness was not ‘normal’- this is a modern standard of normalcy. From this quick look at Buffon’s theory, we can see the ease with which Greek environmental thought can be moulded to garner modern notions of race, with an immediate focus on skin colour. The two societies converge in their view that black skin results from environment – the difference lies in the idealisation of white skin during the enlightenment.

In looking to the implementation of science in theories of beauty, we should consider Camper’s facial angle. Camper (1794, p.32) described a ‘striking resemblance’ between ‘the race of Monkies and Blacks’. His work shows the decline of facial angle moving from Greek and Roman sculpture, to Europeans, to Black people, and to Orang-utan heads (Figs. 10-11). The scientific appeal of Camper’s theory, alongside its adaptability to notions of savagery sealed its fate as foundational to the development of racist theories of aesthetics and anatomy. Camper provided racist theorists with the means to ‘scientifically’ justify the supposed superiority of White Europeans, through appeals to ancient Greece. Charles Bell (1847, pp.25-30), for example, utilised Camper’s work to contrast the heads of ‘perfect’ antique statues with African skulls, concluding that the difference showcased European intelligence and superiority (Figs. 12-13). We see that notions of beauty did not stop at aesthetics, but were used to justify superiority in character. By exploring theories of science and aesthetics, we see the development of ideas of beauty and intelligence in the Enlightenment – concepts inextricably tied to skin colour.

The Legacy of the Savage Barbarian

Ideas of ugliness became tied to themes of savagery amongst Black people, serving, as Bernal (1987, p.241) points out, to justify the abhorrent treatment of Black slaves. In our exploration of Greek literature, we encountered ‘savage’ barbarians. We now explore notions of savagery during the Enlightenment and see, once again, how the implementation of colour in theories of race differentiates them from ancient Greek views of other peoples.

Let us continue with themes of beauty and ugliness, with reference to savagery. Meiners (1785, p,43), as detailed by Jahoda (1999, p.66) held beauty at the centre of his theory, stating that ‘one of the most important characteristics of tribes and people is beauty or ugliness’, describing ‘feeble-minded’ and animalistic ‘ugly peoples’. Jahoda (1999, pp.66-67) notes that Meiners referred to anatomical studies in expressing his view that the colour of Black people governed their capacities, dispositions and temperament. Long (1774, pp.352-353) compared Black people to apes, deeming them ‘bestial’ with a ‘nature even below brutes’, commenting on their ‘flat noses’ and ‘fetid smell’. Jahoda (1999, p.55) points out that Long was a planter in Jamaica, with a vested interest in presenting Black people as savage, so as to dehumanise the slaves that were treated so poorly. Let us think back to the ‘savages’ encountered above. At first glance, these descriptions resemble the ancient ones. I posited no colour prejudice in ancient descriptions, yet claim that enlightenment theories exhibit clear racism and colour prejudice. What, then, differentiates the two?

The first point is that Enlightenment theorists ascribe their descriptions to a Black ‘race’ absent from the Greek world. For the Greeks, barbarians were not classified by skin colour, but custom. There were Black ‘savages’ whose practices were condemned, but also White ‘savages’ who were so condemned. Theorists like Meiners and Long, although they did pay attention to custom, attached a significance to skin colour absent from antiquity.

The second point should be made with reference to the overall aim of this study: to show that the connotations attached to ‘black’ and ‘white’ present in the modern world were absent from the ancient one. The Greeks produced theories, literature and art about people who differed from them, remarking physical and cultural differences – differences used to justify their own superiority. Scholars of the Enlightenment, however, functioned within a society centred around race, which came to hold skin colour at its core. When viewed retrospectively, holding modern notions of race, Greek views about other peoples are easily misunderstood. Their ideas did not lack prejudice, but were made without the relentless post-enlightenment focus on skin colour. The colour terms ‘black’ and ‘white’ became inextricably tied to notions of race, hierarchy, beauty, intellect, and slavery; this was not so in Greece. Theorists of the Enlightenment irreversibly entrenched notions of Blackness and Whiteness into the discourse of race, and used the Greeks to do it.

Ancient Greece Online

Let us move towards the twenty-first century. As Wenger (2017) puts it: ‘the Classical past refuses to stay in the past’. The invocation of Greece to legitimise White supremacy is, as we have seen, not a new phenomenon, nor one confined to the past. White supremacists today continue the practice, begun in the Enlightenment, of inserting issues of colour into antiquity. There is particular focus on identity, with individuals claiming European, Western, or White identity, bolstered by the achievements of the Greeks.

Richard Spencer, a leader of the Alt Right movement, posted a video urging his viewers to realise their White identity through visual allusions to ancient Greece. Spencer (2015) appeals to vague ancestors with strong senses of identity, insisting ‘we are a part of the people’s history, spirit and civilisation of Europe’. Pharos (2021) notes that, as Spencer talks, images of ancient temples, and Aristotle and Augustus, appear on screen (Figs. 14-15). Spencer’s video is symptomatic of the White supremacist’s incessant invocation of Greece to justify White, Western superiority. The video serves to affirm current White greatness through allusion to previous ‘White’ achievements. Knowing what we do about Greece, we know that many of these achievements are not, in fact, ‘White’ at all; moreover, if it were proposed to the Greeks that they were ‘white’, they would be shocked.

Fig. 14. Screenshot from Spencer’s video urging viewers to realise their ‘White identity. Image of an ancient temple and figure from the ancient world. (Spencer, 2015)

Fig. 15. Bell’s contrast of the head of a Black man and the head of M.Agrippa, using Camper’s facial angle. 1847. (Bell, 1847, p.30)

Spencer is not alone in his claim to lineage from some great ‘Western’ or ‘European’ culture. Websites like Identity Evropa, Radix, Euro Canadians, and American Renaissance, among many others, reflect this idea, placing great focus on such identities. Identity Evropa (no date) describe themselves as ‘American Identitarians’ who have ‘realised’ their descent from ‘the great traditions, history, and people that flowed from Europe’. On other sites, you find articles like Discovering the European Mind (2016) and The Collective Brain of Whites Generated All Modern Innovations (2021). These articles, and the many like them, claim European identity through allusion to the Greek world. Obviously, claims to ancient Greece would not serve White supremacists well if they admitted that the Greeks were not ‘White’. So, they distort ancient Greece and insert Whiteness into it, often on the premise that the Left-wing is trying to erase the traditional canon and insert colour where it does not belong. For example, Francis (2015) refers to the Greeks as the ‘old Aryans’ and Sims (2010) asserts two racial types in ancient Greece: ‘dark-haired Whites’ and ‘fair-haired Whites’. This is not the place to dismantle such claims or address the inaccuracy of the evidence supporting them. The important thing to note is the dangerous continuation, from the Enlightenment to present-day, of this obsession with Whiteness and the invocation of Greece to affirm White identity. The distortion of antiquity is as relevant now as it has ever been, and it is integral to confront these misconceptions surrounding skin-colour to prevent further use of Greece to enforce White supremacy.

Conclusion

It is clear that the Greeks were well acquainted with Black people and that comment was made on their skin-colour as, largely, a differentiating feature. It is necessary to understand, however, that this difference was not cause for discrimination. We know that the Greeks were fascinated by things that differed from them, especially following the creation of oppositional self-definition during the Persian wars. Descriptions of black skin were largely superficial, and no real judgements were made on the basis of skin-colour. Observations were in line with environmental theory, and character judgements accompanied observations of black skin; however, these judgements were not made because of black skin itself.

We have encountered both positive and negative descriptions of Ethiopia, seeing particularly negative portrayals in accounts of ‘savage’ Ethiopians. These descriptions showcase a Greek sense of superiority and prejudice towards those who differ culturally. These judgements, however, were not made on the basis of skin colour. The Greeks did place themselves at the top of their own hierarchy, but this was in lieu of their self-conceived cultural superiority. Descriptions of savagery show, at most, that the Greeks believed themselves superior in terms of their cultural practices. The point is that negative depictions of Black people in Greek thought did not entail racism or colour prejudice, because they accompany many positive descriptions, and were not made because of blackness. The evidence shows a fairly balanced view of Ethiopians; although they were represented negatively sometimes, this was true for many, not just those with black skin.

Throughout this essay, I have reinforced the fact that the Greeks did not consider themselves ‘White’, despite modern attempts to paint them as such. This point is important for two reasons. Firstly, it shows the danger of reading Greek antiquity with modern notions of blackness and whiteness in mind. The terms ‘black’ and ‘white’ did not hold the same meaning to the Greeks as they do to us. Whiteness and Blackness became tied to race during the Enlightenment, irreversibly changing the meaning of these terms. If we read the Greek world with these notions in mind, we will misunderstand it, and risk inserting racism or colour prejudice that simply did not exist. Secondly, it reinforces the inaccuracy of the use of Greece to justify White supremacy. Claiming Greek achievements as White ones has been integral to European claims of superiority, both during the Enlightenment and in the twenty-first century. Recognising that the Greeks did not consider themselves as White, we can see the absurdity of people of, for example, British descent claiming Greek achievements as their own. It must be understood that the Greeks did not consider themselves as White in order to prevent the continued misuse of the Greek antiquity to support racist ideas surrounding White supremacy, a practice continuing to this day.

[1] When I use ‘Black’ and ‘White’ with reference to ancient Greece I refer to people whose physical features would place them in those categories today – there was no ‘Black’ race in ancient Greece and the ancient Greeks were not themselves ‘White’.

[2] They identified rather with regions and city-states, and other identities below the linguistic-cultural level of ‘Greeks’ or ‘Hellenes’ that we typically group them under today.

[3] ‘Greek’ was not the only, nor always the most important, identity. It is, however, the most essential to this study.

[4] Isaac (2006, p.60) points out that the work is often attributed to Hippocrates, but it is uncertain whether it was actually written by him.

[5] Sassi (2001, p.23) clarifies that the Greeks burned their dead and the Indians ate them, according to Herodotus.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Aeschylus. 1926. Suppliants, tr. Weir Smyth, H. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Aeschylus. 1926. Prometheus Bound, tr. Weir Smyth, H. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Agatharchides. 1989. On The Erythraean Sea, tr. Burnstein, S. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aristotle. 2011. Problemata, tr. Mayhew, R. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Arrian. 1976. Anabasis of Alexander, tr. Brunt. P. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Diodorus Siculus. 1935. Library of History, tr. Oldfather, C. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Herodotus. 1920. The Histories, tr. Goodley, A. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hesiod. 1914. Theogony, tr. Hugh, G. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, London: William Heinemann.

Hippocrates. 1923. Airs, Waters, Places, tr. Jones, W. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Homer. 1924. Iliad, tr. Murray, A. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, London: William Heinemann.

Strabo. 1903. Geography, tr. Hamilton, H. and Falconer, W. London: George Bell & Sons.

Thucydides. 1843. The Peloponnesian War, tr. Hobbes, T. London: Bohn.

Secondary Sources

Allahar, A. 1993. When Black First Became Worth Less. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 32 (1-2), pp.39-55.

Bell, C. 1847. The Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression As Connected With The Fine Arts. 2nd ed. J. London: John Murray.

Bérard, C. 2000. The Image of the Other and the Foreign Hero. In: Cohen, B. ed. Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Leiden: Brill, pp.390-413.

Bernal, M. 1987. Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilisation: The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Buffon, G. 1766. Histoire Naturelle Générale et particulière avec la Description du Cabinet du Roy. Paris: De L’Imprimerie Royale.

Camper, P. 1794, The Works of the Late Professor Camper on the Connection Between the Science of Anatomy and the Arts of Drawing, Painting, Statuary. London: C. Dilly.

Duchesne, R. 2021. The Collective Brain of Whites Generated All Modern Innovations. [Online] [Accessed 21 April 2022] Available from: https://www.eurocanadians.ca/2021/04/the-collective-brain-of-whites-generated-all- modern-innovations-15.html

Francis, S. 2015. The Roots of the White Man. [Online] [Accessed 29 April 2022]. Available from: https://radixjournal.com/2015/02/2015-2-14-the-roots-of-the-white-man/

Gruen, E. 2011. Rethinking The Other in Antiquity. Princeton, N.J.; Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

Hall, J. 1997. Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Identity Evropa. [no date]. Who we Are. [Online] Available From: https://www.identityevropa.com

Isaac, B. 2004. The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Jahoda, G. 1999. Images of Savages: Ancient Roots of Modern Prejudice in Western Culture. London; New York: Rutledge.

Long, E. 1774. The History of Jamaica. London: T. Lowndes.

McCoskey, D. 2019. Race: Antiquity and Its Legacy. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Meiners, C. 1785. Grundriss der Geschichte der Menschheit. Lemgo: Meyer.

Mitter, P. 2011. Greece, India, and Race among the Victorians. In: Orrells, D., Bhambra, G. and Roynon, T. eds. African Athena: New Agendas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.56-71.

Pharos. 2021. Greco-Roman Antiquity, the Basis of White Identity. [Online] [Accessed 15 March 2022]. Available from: https://pharos.vassarspaces.net/2021/06/04/richard- spencer-who-we-are-white-identity-greco-roman-antiquity/

Radix Journal. 2016. Discovering the European Mind. [Online] [Accessed 3 May 2022]. Available from: https://radixjournal.com/?s=discovering+the+european+mind

Richard Spencer. 2015. Who Are We? [Online] [Accessed 1 May 2022]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20201028163110/https://radixjournal.com/2015/12/2015- 12-11-who-are-we/

Sassi, M. 2001. The Science of Man in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sims, R. 2010. What Race Were The Greeks and Romans? [Online] [Accessed 29 April 2022] Available from: https://www.amren.com/news/2016/10/what-race-were-the- ancient-greeks-and-romans/

Smith, M. 2001. Africa as Renaissance Grotesque: John Skelton’s 1485 Version of Diodorus

Siculus. Shakespeare in South Africa. 13 (1), pp. 23-31.

Snowden, F. 1970. Blacks in Antiquity Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Snowden, F. 1991. Before Colour Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Cambridge, Mass; London: Harvard University Press.

Thomas, R. 2000. Herodotus in Context: Ethnography, Science and the Art of Persuasion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, A. 2017. “Our” “Classics”. Problems of Difference in Western Civilisation. [Online] [Accessed 27 March 2022] Available from: https://eidolon.pub/our-classics- 93292adafbb2