Influence of Affluence and Diversity on Perceptions of Africa: The African Voices Schools Project

By Richard Borowski

Accessible companion page for 'Influence of Affluence and Diversity on Perceptions of Africa'

Introduction

Teaching about the wider world on its own is insufficient to overcome negative perceptions of ‘others’ that can be propagated from one generation to the next within communities and through social and national media. To break this inter-generational perceptual cycle and move towards a society that is more accepting and inclusive, young people need to engage directly with ‘others’ from outside of their own cultural experience before negative perceptions become emotionally lodged and difficult to change in later life (Scoffham, 1999). The opportunities available for young people to enter into such intercultural engagements depend upon their socio-economic status and the ethnic diversity of their local community. Young people from affluent families are more likely to travel beyond their home community and young people who live in ethnically diverse communities are more likely to get to know other young people from different cultural backgrounds (Weigand, 1992). Both these factors appear to positively affect attitudes to cultures outsides one's own.

This article uses evidence gathered by the Leeds University Centre for African Studies (LUCAS) Schools Project to explore young people’s perceptions of the African continent and African people and to demonstrate how family affluence and community diversity influence their perceptions. The primary and secondary schools that participated in the research studies are representative of the diversity and affluence across the city of Leeds. The population if the city is about 800,000 of which about 19% are classified as coming from a Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic (BAME) background. The BAME population of Leeds is not evenly distributed across the city, the majority live in inner-city areas. The average household income in Leeds is slightly lower than the national average with higher income households located in outer-city areas. The LUCAS Schools Project operated in virtually all areas of the city, so the data collected presents a good basis for a comparative analysis.

LUCAS Schools Project

The LUCAS Schools Project (2004-2020) was an outreach initiative that recruited, trained, and supported over 120 African postgraduate students at the University of Leeds to deliver more than 350 African Voices activity programmes to over 9,000 pupils in primary and secondary schools in Leeds about the African continent and its peoples. The development of the African Voices programmes was practice-led, it evolved from the experience gained in the delivery of activities in the classroom and from the evidence gathered of impact assessments. The project’s comprehension of young people’s perceptions of Africa and Africans reflected and corroborated theoretical concepts of ‘otherness’ explored by advocates of theories of postcolonialism (Andreotti, 2007 and Martin & Griffiths, 2012) and infrahumanisation (Leyens et.al., 2000).

Perceptual Baggage

Children learn about other places, peoples and cultures from the adults in their life and from the media they consume. Sometimes, stereotypical views and opinions of 'others' are propagated from one generation to the next without being challenged. In 1985, Edward Said famously wrote about the distorted Eurocentric depiction of Arab-Oriental peoples and their culture in his book Orientalism. In his perceptive analysis, the stereotypical representation of a group of people from another region of the world with different cultural values not only denigrates that group of people but also bolsters the self-esteem of the people who hold those views. The demeaning of others builds a sense of pride and national identity that elevates the propagating culture above others. For any educational programme that involves children learning about a distant place or people from another country or culture it is important to first unpack their perceptions of that place or people and address any misunderstandings and misconceptions. Not to do so could reduce the effectiveness of the learning programme and potentially reinforce stereotypical views and opinions. Activities developed by the African Voices programme created a learning environment through which the pupils could question their own perceptions. A foundation for further learning was established that prepared pupils to accept new knowledge and perspectives without being constrained by their existing perceptual baggage.

Learning to Unlearn

We are the sum of our life experiences. Our views and opinions of ‘others’ are shaped by the people we live amongst and the culture of the society around us. To avoid misunderstandings and misconceptions that could propagate stereotypes and reinforce any prejudice towards ‘others’, this has to be acknowledged by both teacher and learner. Most teaching about ‘others’ from a UK perspective, and in particular ‘others’ in developing regions of the world, is delivered from a privileged position. When engaging with educational resources about ‘others’ we are all susceptible to unconscious bias, interpreting what we read, see and hear from a privileged position. Gayatri Spivak, wrote about unlearning one’s own privilege to engage equitably with ‘others’ (Andreotti, 2007). She later re-phrased this as 'learning to unlearn'. Adults are likely to find ‘learning to unlearn’ more difficult than children do. From about the age of 7/8 to 12/13 years a child’s opinions are still forming and they more likely to incorporate new perspectives into their view of the world than teenagers or adults. Beyond 12/13 years, the views children have formed become emotionally fixed and more difficult to change (Scoffham, 1999). The delivery of African Voices activity programmes overcame the issue of ‘learning to unlearn’ primarily through the engagement of African postgraduates as the teachers. They presented the learning resources from a position of equity rather than privilege. Their knowledge and perspectives of their countries and the continent of Africa came directly from their own experience, unfiltered by unconscious bias.

Third Space

Parachuting in an African postgraduate into the classroom to provide authenticity, and avoid the propagation of misunderstandings and misconceptions, is insufficient without an environment conducive to new learning. The active learning approaches used in the delivery of the African Voices programmes provided the space and time for pupils to engage directly with their African teacher to find out for themselves, first hand, honest and informed answers to the questions they wanted to ask. Homi Bhabha envisaged this learning taking place in a ‘Third Space’ where teachers and learners are prepared to acknowledge their own perceptual baggage, set it aside and engage with new information without prejudice or unconscious bias (Martin & Griffiths, 2011). This also applied to the African postgraduates recruited to deliver the African Voices programmes; it would be wrong to assume that they could engage equitably just because they were from Africa. They had their own perceptual baggage to acknowledge; the legacy of European colonialism had an influence on their perceptions of the UK which meant that they could also hold misunderstandings and misconceptions that could unintentionally propagate stereotypical views. In this respect, the training of the African postgraduates was vitally important; it prepared them to deliver the activity programmes and provided them with an opportunity to explore their own perceptual baggage in preparation for entering Bhabha's ‘Third Space’ with the pupils in the classroom.

In-groups and Out-groups

One of the reasons for the success of the African Voices activity programmes was the personal contact the pupils had with their African postgraduate teachers. During the engagements, it was possible for the pupils to relate to a real person from the place and culture they were learning about. The pupils no longer considered their African postgraduate teacher as ‘other’ and the emotional bond established added validity to the information exchange. The personal connection enhanced the retention of new knowledge acquired and contributed to the embedding of perceptual change.

For example, following the delivery of an African Voices programme a Year 5 focus group was asked a question about what they knew about their African teacher.

The pupils knew Charles was from Kenya, he had three children, more than one mother, suffered from Tennis Elbow and there were 14 members of his family.

When another Year 5 focus group was asked what made them change their minds about African people they responded:

All the information. Ret’sepile didn’t lie, she told us about good and bad things.

Other educationalists have also recognised the value of engaging directly with ‘others’ at an emotional level (Pickering, 2008; Scoffham, 2019) and acknowledge that such approaches are more successful in challenging overly negative stereotypes.

The benefit of this emotional connection between pupils and teacher reflects the theory of infrahumanisation developed by the Belgian sociologist Jacques-Philippe Leyens (2000). Leyens’ theory is based on the belief that people view ‘out-groups’ as less human than their own ‘in-group’ and that this view is reflected in the types of emotions people believe their own ‘in-group’ and other ‘out-groups’ possess. Some, more subtle emotions, are considered unique to humans e.g., love, regret, nostalgia (UHEs), whereas others are viewed as common to both humans and animals e.g., joy, anger, sadness (non-UHEs). Where humans are equated only with non-UHEs they are usually seen as inferior, or 'less human', leading to denigration. Other infrahumanisation researchers have demonstrated that interventions at an early age can increase the attribution of UHEs towards ‘out-groups’ and reduce racial dehumanisation (Vezzali et.al., 2012 and Costello & Hodson, 2014). Based on this model, the African postgraduates, through their engagement programmes, were able to establish emotional connections which took them out of the pupils’ ‘out-group’ and into their ‘in-group’.

Young People’s Perceptions

Over the past 16 years, the African postgraduates recruited by the LUCAS Schools Project have had to address a wide range of misunderstandings and misconceptions about Africa and its peoples held by the young people they taught in classrooms around Leeds.

Perceptions of Africa

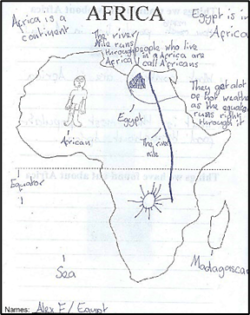

Research undertaken during the development phase of the Schools Project (2007-10), with Year 6 pupils in four primary schools and Year 8 pupils in three secondary schools, revealed the extent of the problem (Borowski, 2012). The limits of knowledge about and perceptions of Africa were evident in what Year 6 pupils wrote or drew about Africa on blank outline maps.

Figure 1 – Perceptions of Africa of Year 6 pupils from Africa Maps in the 2007/10 research study

The pupils perceived the African continent to be hot and dry everywhere and they thought that African people were mainly farmers living in informal dwellings with little access to clean water. There was little awareness of the diversity of climate and landscape or of urban life and industrial activity. There were many references to wild animals, music and dancing and images of tropical fruits and cash crops such as cocoa. These were a reflection of wildlife documentaries and travel programmes depicting exotic cultures and of lessons on fair trade at school. The evidence gathered from the map activity demonstrated that pupils had limited and distorted knowledge about Africa. The results were also a reflection of the stereotypical perceptions of the African continent and its peoples propagated within local communities and via national media.

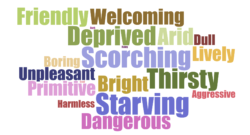

The research undertaken between 2007/10 also investigated young people’s linguistic and visual perceptions of Africa. When asked to choose three words from a selection they thought would best describe Africa, both the Year 6 and Year 8 pupils chose words such as scorching, arid, thirsty, starving, deprived and primitive, confirming perceptions of Africa that were evident from the just-mentioned Africa maps.

Figure 2 – Linguistic Perceptions of Africa of Year 6 and Year 8 pupils in the 2007/10 research study

Year 6 Pupils Year 8 Pupils

The size of the word represents the frequency of choice.

However, there was also an indication in the results that the pupils felt unthreatened by Africa. Whilst being less common, the pupils chose words such as friendly, welcoming and lively. In addition, it is notable that more Year 8 pupils chose words such as unpleasant and aggressive than the Year 6 pupils.

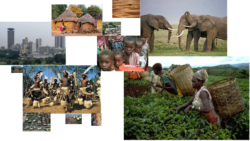

When asked to choose three images they thought best showed what Africa looked like both the Year 6 and the Year 8 pupils chose pictures of hungry children, tea pickers, rural housing and traditional dancers, which also confirmed their perceptions of Africa evident in the Africa maps.

Figure 3 – Visual Perceptions of Africa of Year 6 and Year 8 pupils in the 2007/10 research study

Year 6 Pupils Year 8 Pupils

The size of the image represents the frequency of choice.

What was most disturbing about the findings was dominance of images such hungry children and rural housing. Both these images are a feature of charity campaigns, seeking financial support for their relief and development work, and news reports of famines and natural disasters. They make a significant contribution to the stereotypical and distorted perception young people hold about Africa and its peoples.

In addition to the investigations into the pupil’s linguistic and visual perceptions of Africa, the research also assessed their knowledge about Africa. When presented with a range of agree/disagree statements about Africa, most Year 6 pupils thought of Africa as a place where there are no tall buildings, where people have little food to eat, have no access to TVs and do not use mobile phones. There was little recognition of the urban, industrial, and technological aspects of the continent or the accomplishments of African people.

Perceptions of Africans

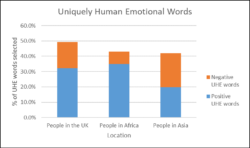

In 2010/11, the Schools Project undertook a comparative research study, with Year 6 pupils in five primary schools, of their emotional expressions towards people in the UK, people in Africa and people in Asia. The focus of the investigation was to determine whether young people could express infrahumanisation (Leyens, 2000). In particular, the study sought to find out the extent to which 10-11 year olds expressed uniquely human emotions (UHEs) towards people like themselves and non-uniquely human emotions (non-UHEs) towards people they considered as ‘others’?

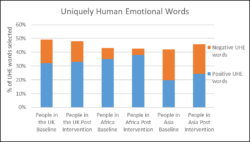

From a selection of words, both positive and negative, the pupils chose as many as they wanted to describe people in the UK, Africa, and Asia. Within this selection, there were UHE words non-UHE words, competency words and sociability words (Appendix I). The overall findings indicated that young people of 10-11 years old could express infrahumanisation towards people in Africa and Asia. The pupils chose a greater percentage of UHE words to describe people in the UK than they did to describe people in Africa or Asia.

Figure 4 – Percentage of UHE words chosen by pupils to describe people in the UK, Africa, and Asia in the 2010/11 research study

According to Leyens, the pupils were including people in the UK in their ‘in-group’ and people in Africa and Asia in their ‘out-group’. However, when their choice of UHE words was analysed in terms of the positive and negative words chosen, the pupils chose a greater percentage of positive UHE words to describe people in Africa.

Figure 5 – Positive and negative UHE words chosen by pupils to describe people in the UK, Africa, and Asia in the 2010/11 research study

People in the UK People in Africa People in Asia

The size of the word represents the frequency of choice.

This supported the findings of the 2007/10 research study. Choosing more positive UHE words to describe people in Africa indicates that the pupils felt less threatened by people in Africa compared with people in the UK and Asia.

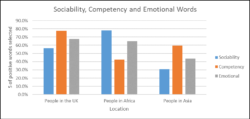

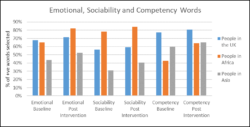

The research study in 2010/11 also generated other findings that corroborated the findings of the 2007/10 research study and provided further insight into the perception young people have of ‘others’.

Figure 6 – Percentage of positive sociability, competency and emotional (UHE and non-UHE) words chosen by pupils to describe people in the UK, Africa, and Asia in the 2010/11 research study

For example, the pupils chose a greater percentage of positive emotional words, UHE and non-UHE words, to describe people in the UK and Africa than to describe people in Asia. In addition, the pupils considered people in the UK to be more competent than people in Africa or Asia and people in Africa to be more sociable than people in the UK or Asia.

Whilst these results were consistent with the findings from the 2007/10 research study, in terms of competency, the response from pupils regarding their thoughts about the sociability of people in Africa required further consideration. On the surface, the sociability finding indicated a very positive perception of people in Africa. However, even though the earlier study found overly negative perceptions and stereotypical views about Africa, the pupils in this study thought African people to be more sociable than people in the UK or Asia. It created an interesting perceptual construction. On the one hand, the pupils perceived Africa to be inferior and lacking in comparison to the UK, and African people to be less competent than people in the UK. On the other hand, they considered African people to be more sociable than people in the UK. This combination of emotion and sociability could be a result of the impact charity campaigns on young people that convey a sense of poverty and helplessness to engender sympathy and compassion towards people in Africa.

Influence of Affluence and Diversity

The data gathered for the research studies in 2007/10 and 2010/11 was further analysed by school and the findings considered in relation to the socio-economic status of the pupils and ethnic diversity of their local community. This revealed further evidence of the extent and degree of distorted perceptions of Africa amongst young people in Leeds and demonstrated that it was not uniform across the city.

Perceptions of Africa

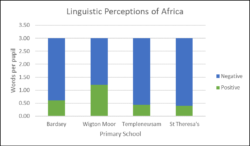

Analysis of the 2007/10 research study in primary schools revealed that young people from more affluent backgrounds living in multi-ethic communities had a more positive perception of Africa.

Figure 7 – Affluence and diversity of primary schools in the 2007/10 research study

| Primary School | Local Average Income[1] | Free School Meals[2] | Local area BAME[3] | English as First Language[4] |

| Bardsey | £37.0K | 4.6% | 7.0% | 92.9% |

| Wigton Moor | £34.4K | 9.2% | 27.3% | 54.2% |

| Templenewsam | £31.5K | 21.6% | 10.1% | 97.3% |

| St Theresa’s | £31.4K | 16.2% | 7.9% | 89.0% |

Figure 8 – Positive and negative words chosen per pupil to describe Africa by primary school in the 2007/10 research study

Of the four primary schools in the 2007/10 study, the pupils at Wigton Moor primary school were the most positive about Africa, choosing a greater percentage of positive words to describe Africa than pupils at the other three research schools did. Two factors contributed towards this finding. Firstly, Wigton Moor primary school is located in the relatively affluent Alwoodley area of Leeds. Young people attending Wigton Moor were more likely to engage with other cultures through international travel (Weigand, P. 1992). Secondly, there was a diverse ethnic community in the catchment area around Wigton Moor. The BAME community in Alwoodley was not homogeneous, it represented a wide range of race, culture, and religion[5].

Bardsey primary is also in a relatively affluent area of Leeds, it is a village school on the outskirts of Leeds, but the BAME population in the area was the lowest of all the four schools in the study. Affluence appeared to have had an impact on the pupil’s perceptions of Africa but not as great an impact as ethnic diversity.

The pupils at Templenewsam and St Theresa’s primaries were the least positive about Africa. Both these schools are located in areas of Leeds with an average household income and a BAME population lower than Wigton Moor. The pupils at these two schools had fewer opportunities to engage with other cultures and, consequently, were more reliant on the views and opinions of their local community and the portrayal of Africa in the media.

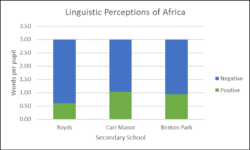

The evidence gathered from the secondary school study corroborated the findings from the primary school study. Overall, the secondary school pupils were more positive about Africa but the impact of affluence and diversity was evident.

Figure 9 – Affluence and diversity of secondary schools in the 2007/10 research study

| Secondary School |

Local Average Income[1] | Free School Meals[2] | Local area BAME[3] | English as First Language[4] |

| Benton Park | 33.1K | 19.70% | 5.10% | 96.10% |

| Carr Manor | 29.9K | 40.70% | 31.20% | 70.90% |

| Royds | 31.8K | 45.20% | 5.20% | 96.50% |

Figure 10 – Positive and negative words chosen per pupil to describe Africa by secondary school in the 2007/10 research study

Both Benton Park and Royds secondary schools are in areas of Leeds with similar levels of household income to Templenewsam and St Theresa’s in the primary school study but have a lower percentage of BAME residents. In addition, the high percentage of free school meals at Royds secondary indicates a wide income gap between the most and least affluent. This disparity in community affluence could explain why the pupils at Royds secondary school were less positive about Africa than the pupils at Benton Park secondary.

Carr Manor secondary school is similar to Wigton Moor primary in that it had a diverse ethnic community in the catchment area. However, Carr Manor is an inner-city school in the Moortown area of Leeds where the residents are less affluent than those of the Alwoodley area. This lack of affluence appears to mitigate the benefits gained from the ethnic diversity of Carr Manor.

Perceptions of Africans

Analysis of the 2010/11 research study provided further evidence of the impact of affluence and diversity on pupil’s perceptions of African people. Within this study, the pupils were asked for their perceptions of African people rather than their perceptions of Africa.

Figure 11 – Affluence and diversity of schools in the 2010/11 research study

| Primary School | Local Average Income[1] | Free School Meals[2] | Local area BAME[3] | English as First Language[4] |

| St Theresa’s | £31.4K | 16.2% | 7.9% | 89.0% |

| Kirkstall St Stephen's | £29.8K | 27.1% | 21.9% | 92.1% |

| Queensway | £27.8K | 42.6% | 5.1% | 94.3% |

| St Bartholomew's | £22.2K | 45.6% | 22.0% | 42.5% |

| Windmill | £21.9K | 65.4% | 11.8% | 72.0% |

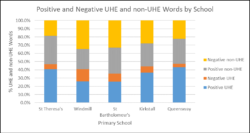

Figure 12 – Percentage of UHE and non-UHE Words chosen by pupils to describe African people by primary school in the 2010/11 research study

Of the five primary schools in the 2010/11 study, the pupils at St Theresa’s and Queensway primaries were the most positive about African people. These two primary schools are at the opposite sides of the city but have similar economic and ethnic characteristics. They are both in areas of Leeds with an average household income and lower than average BAME population. It is pertinent to note that the households around St Theresa’s primary had the lowest average household income in the 2007/10 research study but had the highest average household income in the 2010/11 research study. Even though the pupils at St Theresa’s were the least positive about Africa in the 2007/10 study, they were the most positive about African people in the 2010/11 study.

Kirkstall is an inner-city area of Leeds with a similar level of household income to St Theresa’s and Queensway but a higher than average BAME population. Given the influence of affluence and diversity on perceptions of Africa observed in the 2007/10 study, a higher positivity was expected. However, Kirkstall has two primary schools, Kirkstall St Stephens, the one in the study, and Kirkstall Valley. BAME parents preferred to send their children to Kirkstall Valley primary and non-BAME parents preferred to send their children to Kirkstall St Stephen’s primary. Consequently, the percentage BAME pupils at Kirkstall St Stephen’s was not representative of the local community. This self-segregation of children from different ethnic backgrounds appeared to have a negative impact on the perceptions the pupils had of African people.

The pupils at Windmill primary and St Bartholomew’s primary were the least positive about African people for very different reasons.

Windmill primary school is in the Middleton area of Leeds with a lower than average household income and a lower than average percentage of BAME residents. Of all the schools in the 2007/10 and 2010/11 studies, the pupils at Windmill were the most disadvantaged and had the least opportunity to engage with other cultures. Their perceptions of African people reflected a stereotypical narrative of Africa prevalent in their local community and reinforced by the media portrayal of the continent.

St Bartholomew’s primary is in the Armley area of Leeds and is similar to Windmill primary in that the household income of local residents is lower than average. However, there is a higher than average BAME population in Armley which predominantly consists of Muslims from Pakistan and Bangladesh. Given the influence of affluence and diversity on perceptions of Africa observed in the 2007/10 study, a higher positivity was expected at St Bartholomew’s primary in comparison to Windmill primary. However, it appeared that the presence of BAME pupils from a specific ethnic / cultural group did not provide the diversity of culture required to enhance the pupils’ perceptions of African people.

Impact of African Voices Programmes

Perceptions of Africa

The result from the 2007/10 research study, following their African Voices programmes, indicated that the African postgraduates had a significant impact on pupil perceptions of the African continent.

Figure 13 – Linguistic Perceptions of Africa of Year 6 and Year 8 pupils in the 2007/10 research study post-delivery of an African Voices programme

Year 6 Pupils Year 8 Pupils

The size of the word represents the frequency of choice.

Whilst Year 6 pupils still chose words such as Scorching, Starving, Arid, Thirsty and Primitive their frequency of choice was reduced following the delivery of African Voices programmes. They were replaced by words such as Welcoming, Friendly, and Lively which reflected the personal bond the African postgraduates were able to establish with their pupils. It was noticeable that the change was less pronounced following the delivery of an African Voices programme with Year 8 pupils. This may be because pupil’s perceptions are harder to change as they become older (Scoffham, 1999) or it could be a reflection of the difficulties the African postgraduates encountered in establishing a person bond with the pupils within a secondary school structure where more rigid timetables often meant shorter periods of interaction than in the primary schools.

Figure 14 – Visual Perceptions of Africa of Year 6 and Year 8 pupils in the 2007/10 research study post-delivery of an African Voices programme

Year 6 Pupils Year 8 Pupils

The size of the image represents the frequency of choice.

The African Voices programmes had a significant impact on the Year 6 pupil’s visual perceptions of the African continent. The number of pupils selecting the image of hungry children reduced significantly and the image of rural housing was replaced by a city landscape reflecting an urban perspective of the continent presented by the African postgraduates. This degree of change in visual perceptions was not observed with the Year 8 pupils. Images of hungry children and rural housing were still dominated following the delivery of an African Voices programme. This corroborates the finding from the linguistic perceptions activity and raises the same questions about the effectiveness of the intervention with this age group.

Focus group discussions with Year 6 pupils suggested several factors contributed to the observed perceptual changes. The presence of a highly educated, relatively wealthy, and articulate African postgraduates in their classroom challenged pupil’s stereotypical perceptions of what they thought of African people. The pupils had a whole day to establish a personal bond with their African postgraduate which added credibility to what they taught. Also, the activity-based structure of the programme facilitated interaction between African PG student and pupils enabling them to present a balanced perspective of their home country and the continent of Africa.

“I didn’t know they had cars, I thought they had to walk.”

“I learnt that there are wealthy people in Africa as well.”

“I didn’t know that there was that much technology in Africa.”

“I thought all the buildings would be different but they were like what we’ve got.”

Quotes from pupils (2009)

The results showed that direct contact with someone from Africa could dispel the stereotypical perceptions young people had about the continent. It was clear from my discussions with pupils that the new knowledge and information they gained from their interaction with their African postgraduates made them think more critically about their existing perceptions. In my own experience, as a writer of teaching resources about Africa and as a Development Education teacher trainer for the past 20 years, the African postgraduates presented a more effective approach to changing perceptions of Africa than any teaching pack or Continuing Professional Development course.

The results also showed that all pupils had a more positive perception of Africa following the delivery of their African Voices programmes, with the greatest impact being observed in pupils from schools in less affluent areas of Leeds. The African postgraduates presented a perspective of Africa that the young people in these localities had not previously been exposed to through the media and a perspective which they were prepared to acknowledge and incorporate into their perceptions of the continent. In addition, analysis of the results between schools indicated that, regardless of their starting point, the African postgraduates were successful in raising pupil awareness of Africa to roughly the same level in all schools.

Perceptions of Africans

The evidence gathered in the 2020/11 research following the delivery of the African Voices programmes indicated that the delivery of interventions designed to address misunderstandings and misconceptions about Africa and its peoples had no significant impact on the infrahumanisation expressed by 10/11 year olds towards people in Africa.

Figure 15 – Percentage of positive and negative UHE Words chosen by pupils to describe people in the UK, in Africa and in Asia following the delivery of an African Voices programme in the 2010/11 research study

However, the African Voices programmes did have an impact on the positivity of young people towards people in Africa, emotionally and in terms of competency and sociability. In addition, the African Voices programmes also had a similar, but lesser, impact on the positivity young people expressed towards people in Asia.

Figure 16 – Percentage of positive Emotional, Sociability and Competency words selected by pupils to describe people in the UK, in Africa and in Asia following the delivery of an African Voices programme in the 2010/11 research study

The African Voices programmes were successful in changing the perceptions of young people in all the research schools towards people in Africa, and Asia, with the greatest change being observed in schools in the least affluent areas of Leeds. However, the lack of change in the expression of infrahumanisation was disappointing. The pupils did not attribute more UHE characteristics to people in Africa and continued to see people in the UK as more human than people in Africa. This finding would suggest that the subconscious emotional belief of ‘others’ being different and apart is deeply rooted and difficult to change with a limited intervention such as an African Voices activity programme.

The Last 10 Years

Educational Engagement Evaluation

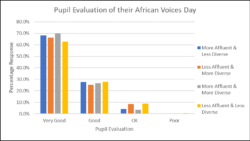

Between 2012 and 2019 the African postgraduates delivered 233 African Voices activity days in primary schools reaching over 7000 pupils in the Leeds area. The impact of the African Voices programmes delivered to Year 5 and Year 6 classes (118) was evaluated on behalf of the University of Leeds Educational Engagement Programme. The overall results indicated that 93% of the pupils thought that their African Voices days were either very good (68%) or good (25%).

Analysis of the data in terms of average household income in the area, the percentage of pupils receiving free school meals at the school, the percentage BAME population in the area and the percentage of English language first speakers at the school indicated that pupils were more likely to consider their African Voices day to be very good if they attended a school that had the following characteristics:

- Schools located in areas of Leeds where the average household income was above £30,000.

- Schools where less than 20% of the pupils were on fee school meals.

- Schools located in areas of Leeds where the BAME population was less than 20%.

- Schools where more than 80% of the pupils in the class spoke English as a first language.

In addition, pupils whose parents or carers had attended University were more likely to consider their African Voices day to be very good.

Further investigation of the evaluation data, in terms of affluence and diversity, confirms the findings from the analysis of the research data. Pupils attending schools in more affluent and more diverse areas of Leeds were most positive about their African Voices days.

Figure 17 – Pupil evaluation of their African Voices Day in terms of whether the pupils are more affluent & less diverse or less affluent and more diverse.

However, of the 118 Year 5 and Year 6 classes included in the evaluation only one class could be assigned to the more affluent and more diverse category. This confirms observations from the analysis of the research data, that BAME populations in Leeds are not evenly distributed across the city and are most likely to be located in the least affluent areas.

African Voices Days Reflections

At the end of each African Voices Day the African postgraduates asked the pupils to complete a reflective questionnaire which was designed to embed learning and enable pupils to self-acknowledge how their own ideas and views had changed. The questions included:

- What did you find most interesting?

- Was there anything in particular that made you think differently about Africa?

- What surprised you?

- What confused you?

- How have your ideas / views about Africa changed?

The pupil responses to these questions varied from school to school because the African Voices programmes developed and delivered by the African postgraduates differed in content. They reflected the postgraduate’s own personal knowledge and experience of the continent and their country of birth. However, there were several common responses which reappeared in the reflective questionnaires each year. Pupils commented on the following:

- The size of the continent and the number of African countries.

- The extensive use of mobile phones and technology.

- The diversity of landscape, climate, culture and language.

- The abundance of mineral and agricultural resources.

- The unfairness of trading relationships.

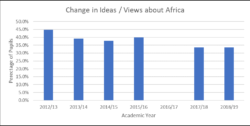

One common objective of all the African Voices programmes was to challenge the stereotypical narrative of Africa propagated advertisements used by charities such as Oxfam and Water Aid. The reflective questionnaires were therefore analysed in terms of how the pupil’s ideas and views about Africa being poor had changed as a result of their African Voices day. Questionnaires completed by Years 5 and 6 pupils during the period 2012 to 2019 were analysed and the percentage of pupils who mentioned something about Africans being less poor than they first thought or acknowledging that there were rich people in Africa as well as poor ones, was calculated for each academic year.

Figure 18 – Pupil reflections on their African Voices Day in terms of the percentage of pupils that included something about Africa being richer or less poor than they first thought

The results show a slight decline in the percentage of pupils acknowledging that Africa was richer, or not as poor as they first thought, between 2012/13 and 2018/19. There could be two possible reasons for this change. Firstly, the stereotypical narrative of Africa could have become less prevalent in wider society during this period. Or, the LUCAS Schools Project was having an impact on the schools that repeatedly requested African Voices days. Without a control group one can only speculate on the reason for this decline. However, the overall analysis of the questionnaires indicates that the stereotypical perception of African is still widespread amongst young people and continues to be intergenerationally propagated.

Conclusion

In the article I wrote in 2012 for Race Equality Teaching (Borowski, 2012) I concluded that television programmes, news reports, films about Africa and charity campaigns all contribute to maintaining a stereotypical myth of Africa and its peoples. Whilst I still believe this to be true now, as it was then, the evidence presented in this article suggests that the perceptions young people have about Africa and its peoples is also as much about how information about Africa is received and interpreted. Young people are the sum of their limited experiences and they attempt to make sense of the world around them from the knowledge, views, and opinions they have acquired. Those young people who have had the opportunity to engage with others of a different race, from a different culture background or a different religious belief are more likely to be accepting of ‘others’.

Young people from affluent families are more likely to have had the opportunity to travel, to meet people from outside of their local community and experience other cultures. They are also more likely to be exposed to the liberal values and attitudes associated with a professional and highly educated community. Conversely, young people from less affluent families are less likely to have these opportunities, their perception of the world is constrained by their lack of experience and they are more reliant on the information and views they acquire from the media and their own community.

The BAME community in Leeds is not evenly distributed, the majority live in some of the least affluent areas of the inner city. In addition, BAME residents of a similar cultural background are more likely to live together in same locality. This ethnic clustering reduces the opportunity for young people in these communities to experience a diversity of cultures. Conversely, young people living in areas of Leeds where there is ethnic diversity have a greater opportunity to meet people from outside their own cultural group within their own community. However, this social construction is intrinsically linked with affluence. The BAME residents in these communities have the wealth to move away from those areas of Leeds associated with their cultural background.

These two factors, affluence and diversity, have a significant impact on how young people perceive Africa and Africans. When affluence and diversity come together, young people have perceptions of Africa that are more positive. When they do not, young people are more likely to retain and propagate stereotypical perceptions of the continent and its peoples.

Analysis of the impact evaluation forms collected over the past 10 years provide support for the conclusions of this article. Pupils from more affluent backgrounds attending more diverse schools were more likely to be positive about their African Voices day. However, analysis of the reflective questionnaires collected over the past 10 years suggests that a stereotypical perspective of the African continent and its peoples is still prevalent amongst young people.

References

Andreotti, V. 2007. An Ethical Engagement with the Other: Spivak’s ideas on Education. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 1, pp. 69-79.

Borowski, R., 2012. Young People's Perceptions of Africa. Race Equality Teaching, 30(3), pp.24-27.

Costello, K., & Hodson, G. 2014. Explaining dehumanization among children: The interspecies model of prejudice. The British journal of social psychology, 53,pp.175-197.

Leyens, J.P., Paladino, P.M., Rodriguez-Torres, R., Vaes, J., Demoulin, S., Rodriguez-Perez, A. and Gaunt, R., 2000. The emotional side of prejudice: The attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), pp.186-197.

Martin, F., & Griffiths, H. 2012. Power and representation: a postcolonial reading of global partnerships and teacher development through North–South study visits. British educational research journal, 38(6), pp. 907-927.

Pickering, S. 2008. What do children really learn? A discussion to investigate the effect that school partnerships have on children’s understanding, sense of values and perceptions of a distant place. Geography Education, 2(1), Article 3. https://www.geography.org.uk/download/ga_geogedvol2i1a3.pdf

Said, E., 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon.

Scoffham, S. 1999. Young Children’s Perceptions of the World. In: David, T. ed. Teaching young children. SAGE, pp. 111-124.

Scoffham, S 2019. The world in their heads: children’s ideas about other nations, peoples and cultures. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(2), pp. 89-102.

Vezzali, L., Capozza, D., Stathi, S., & Giovannini, D. 2012. Increasing outgroup trust, reducing infrahumanization, and enhancing future contact intentions via imagined intergroup contact. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology., 48(1), pp. 437-440.

Wiegand, P (1992) Places in the primary school. London. Falmer

Appendix I

Words that pupils could choose to describe people in the UK, Africa and Asia

| Non-UHE | UHE | Sociability | Competency | |

| +ve | Joyful | Humble | Kind | Skilled |

| +ve | Exciting | Loving | Considerate | Clever |

| +ve | Caring | Sympathetic | Friendly | Powerful |

| -ve | Angry | Regretful | Cruel | Clumsy |

| -ve | Miserable | Arrogant | Aggressive | Ignorant |

| -ve | Frightening | Spiteful | Selfish | Helpless |

[1] Office for National Statistics - https://www.ons.gov.uk/

[2] Gov.UK - https://get-information-schools.service.gov.uk/

[3] Leeds Observatory - https://observatory.leeds.gov.uk/children-and-young-people/

[4] Gov.UK - https://www.compare-school-performance.service.gov.uk/find-a-school-in-england

[5] 14.2% Jewish, 6.0% Muslim, 4.0% Sikh, 3.2% Hindu, 0.4% Buddhist - Leeds Observatory